The US has a rich tradition of Jewish theatre – but in the UK it’s been more circumspect. Artists from Hofesh Shechter to Tracy Ann Oberman explain why

Iask the Israeli-born, British-based choreographer Hofesh Shechter if he considers himself a particularly Jewish artist. He sighs, then nods assent. “Unfortunately.” It’s perhaps the ultimate Jewish answer – sardonic, sorrowed, self-aware, all in a single word.

In a time of bristling identity politics, witty reluctance sounds incongruous. But, on the British stage at least, Jewishness is that kind of label. Jewish theatre artists have been central but often unidentified. Is this an immigrant people’s anxiety around unwelcome attention? “We’re a self-effacing community,” says playwright Samantha Ellis, “we’re afraid to put our heads above the parapet.” Harold Pinter is the most influential 20th-century British playwright, yet the starry retrospective of his work in the West End hasn’t prompted much discussion of his Jewish heritage.

“I think the British Jewish voice is there but we’ve been ashamed of it and kept it under wraps,” says Tracy Ann Oberman when we meet. She pulls out a flask of chicken soup, grimacing cheerily at the cliche. “I grew up in a generation where we, particularly the females, were led to believe that if people in the industry knew you were Jewish it would impact on your casting,” she says. Her drama school suggested she anglicise her surname, “because you don’t look enough like Anne Frank to be cast as a Jew”. Yet, auditioning for a BBC Pride and Prejudice, she was told: “We’d love to have you, but no one really looked like you in Jane Austen’s age.”

Jewish writers often hide their identity … the good Jew is a bleached Jew. It’s incredibly depressing!

Tellingly, a major research project into British Jewish theatre, called Hyphenated Cultures, is a German-Israeli collaboration, which held an international conference last autumn. There’s a far more mainstream American tradition rooted in New York. Authors of brawling intelligence such as Tony Kushner and Paula Vogel follow in the footsteps of Arthur Miller and Clifford Odets to write from a place of cultural confidence. There’s even an American audience for Yiddish versions of classics such as Waiting for Godot or Death of a Salesman. In Britain, it’s less clear who makes “Jewish” work – or who necessarily recognises it as such. “There are hundreds of Jewish people just doing their jobs across theatre,” says Eleanor Turney, who co-directs the annual Incoming festival of emerging talent. The European tradition from which most British Jews come means that visibility is readily elided. “You have to own it,” she continues, “to say: by the way, I’m Jewish – in a way that I don’t think a lot of other minorities do. But there is something interesting in the fact that it is invisible.”

Natalie Abrahami, soon to direct the East Berlin thriller Anna at the National Theatre, looks baffled when I ask if she recognises a strain of British Jewish theatre. Her parents are Israeli and she identifies as culturally Jewish (“I’ve never been to synagogue”), but insists “I hate any labels of any sort. In the same way I don’t identify myself as a female director. That wouldn’t be how I think about the way I make work.”

So where is the British Jewish voice on stage? There’s a fierce line of classical actors – including Janet Suzman, Sara Kestelman, Henry Goodman and Antony Sher – whose journals about playing Shakespeare, from Richard III to King Lear, are revealingly anxious about tackling high-status roles while feeling undeservingly low-status. Was David Lan’s Young Vic – internationalist, restlessly curious – a Jewish theatre? Or Nicholas Hytner’s National Theatre?

Writers who centre their work in Jewish stories – such as Arnold Wesker, Bernard Kops or more recently Julia Pascal, whose new play Blueprint Medeapremieres at the Finborough theatre in May – can be edged from the repertoire. Pascal has also researched Jewish female characters on the postwar British stage – or their absence. “No one is interested in Jewish women,” she declares. “Jewish writers often hide their identity and write about areas that are not to do with their own ethnicity. It comes from a place of fear – don’t draw attention, it’s dangerous.” Often, she notes, Jewish female characters are converts: “The good Jew is a bleached Jew. It’s incredibly depressing!”

Identifying ethnicity in movement is even more elusive. Since arriving in London in 2000, Hofesh Shechter has been a crucial presence in British contemporary dance. Alongside occasional theatre projects – including a folk-tinged Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof – his works are politically questing and often blackly humorous (the recent Grand Finaletook a Titanic-like slide into disaster). Could he define his Jewish sensibility? “I think there is something about the humour, which some people don’t see,” he says, “and about the sarcasm. The darkness but at the same time the lightness – it’s horrible, we’re all going to die, but hey, let’s go out with a bang.”

The Jewish theatrical tradition here is predominantly secular. “Not everybody has a comfortable relationship with Judaism,” Turney observes, “though a writer might find it a usefully antagonistic religion.” Some younger Jewish theatre artists do dip a toe into unfamiliar corners of the orthodox experience (quite literally with the bathhouse settings for Nick Cassenbaum’s Bubble Schmeisis, and The Mikvah Project by Josh Azouz). Others use it as a starting point – Nina Raine’s Tribes was initially prompted by the orthodox Jews of Williamsburg, New York – but subsume the inspiration.

Another concern is around universality – does defining a work as Jewish limit it? “I’ve got very mixed feelings about it,” admits Samantha Ellis. The playwright grew up in an Iraqi refugee family, and contributed to the Paddington movies, an irresistible immigrant myth. “When the refugee narrative became a big part of the story, we talked a lot about it. There’s probably nothing Jewish in these stories, but… ”

Getting her own plays produced has involved responses that reveal theatres’ uncertainty about Jewish material. She has felt the pressure to portray an underrepresented community positively. “I was actually told by a literary manager that Cling to Me Like Ivy was an antisemitic play, because it was critical of a very specific debate in the orthodox community. It’s an astounding thing to be told, and hard to defend yourself against.” She insists: “I reserve the right to write whatever I want.” When asked if the heroine of How to Date a Feminist hadto be Jewish, Ellis replied, “Why shouldn’t she be?” She sighs. “I found that question impossible to answer – and ridiculous.”

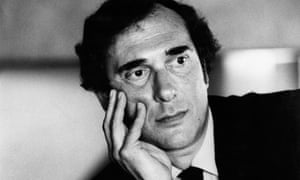

Can Jewish writers find a forebear in Harold Pinter? Britain’s most lauded Jewish playwright often sounded diffident about his heritage. Emerging in a mid-century environment coloured by concerns over immigration and persecution, perhaps it felt pressing to mask differences? “Pinter never writes a Jewish woman character, as I understand it,” says Pascal. Early drafts of The Homecoming explicitly portray a Jewish family, she adds. “There are references to barmitzvahs and chopped liver, but he bleaches that out.”

Ten years after his death, can we now celebrate Pinter as a Jewish writer? “It informs so much of his work and his writing,” argues Oberman, fresh from the West End Pinter season. “Every Jew in this country, post-Holocaust, must have felt ‘we’re a hair’s-breadth away from being called a filthy yid, from being chucked out again.’ That feeling of needing to fit in, yet always being on the outside, I think that’s what gives them such a strong voice.”

Oberman’s own voice has recently become ever stronger, impelled by starring in a 2017 production of Fiddler on the Roof, a musical that has long been significant in diaspora identity. She researched her great-grandparents, whose socialism got them booted out of Belarus. Reclaiming the musical from a fug of heimish comfort ignited her awareness of not only a Jewish performing tradition, but an activist one.

“Fiddler at Chichester was a seminal moment in owning my culture and who I was,” she says. “We worked so hard to make it about all immigrants but also about what happens when this living, breathing Jewish community gets ripped apart and scattered to the four winds. At a time when Labour was turning its back on its Jews, it was a timely reminder that most British Jews came from these shtetls with huge socialist and communist backgrounds.”

The research has also bolstered her stand against antisemitism in Corbyn’s Labour party. “The tradition that my family grew up with in the East End was so much part of the Labour tradition. I love the Labour party, but I started to see the narrative change and found it deeply upsetting.” She began rebutting newly exhumed slurs on social media; she and broadcaster Rachel Riley are currently exploring legal action against up to 70 Twitter users over targeted abuse. She is also developing a gender-switched Shylock in a version of The Merchant of Venice to be set in the East End in the 1930s.

Such public engagement, Oberman insists, can’t be separated from professional visibility. “I’ve got a high-profile friend,” she tells me, “who said, ‘I wouldn’t put myself on the line. I always get cast as Jews and I don’t want to affect my casting.’” She finishes her soup. “I was nervous, but if you’re at ease with yourself and speak out in an authentic way, the industry respects you for it. It’s inauthenticity that they don’t respect.”

Leave a comment