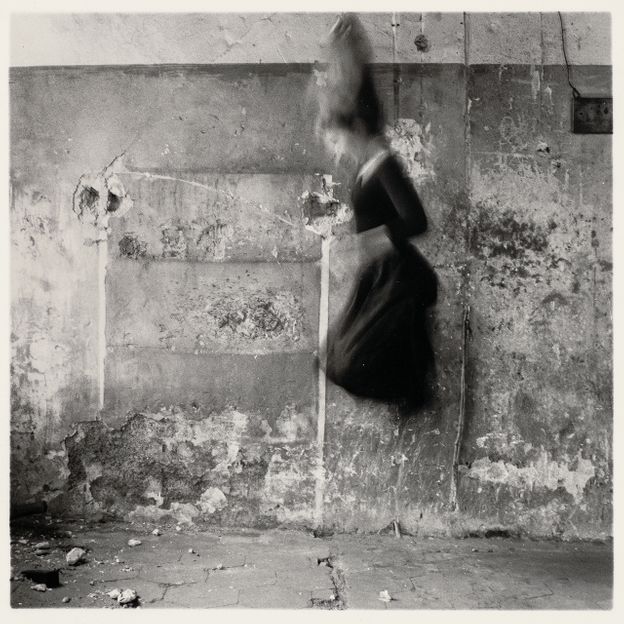

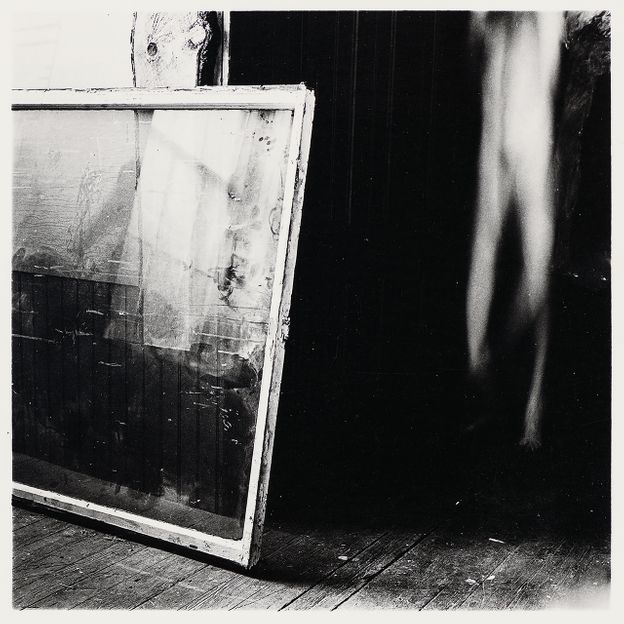

At first glance, the photograph looks straightforward enough. We're in a domestic interior of some kind. A large pane of glass leans against the wall; a dark doorway is behind. The paint is peeling, the floorboards dusty. Then you notice the apparition – a blurred shape approximately identifiable as human. Whoever this person is, they appear to be dangling from above the frame, or possibly leaping down into it. A glitch with the film? A ghost transforming itself from ectoplasm into human form?

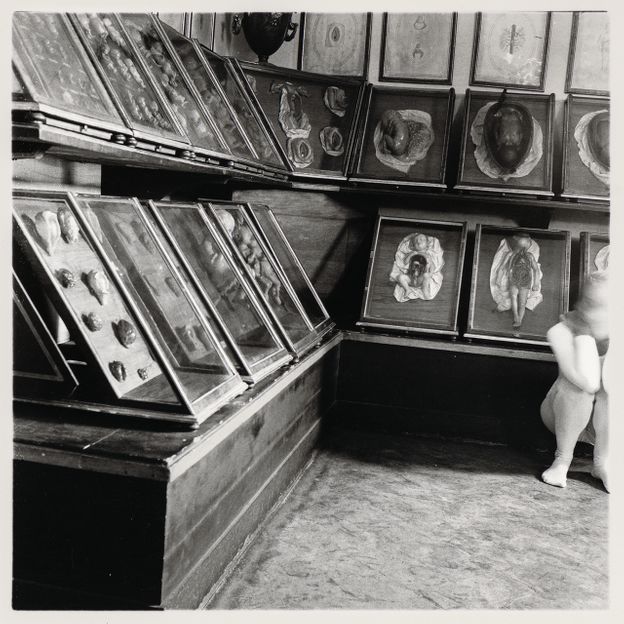

Another picture is even stranger. This one is of an old anatomical museum with glass cases on the wall displaying waxwork foetuses. Yet the most disturbing thing on view is the figure clad in a white leotard far-right, crouching on the floor with her arms bunched around her neck. She seems to be in deep distress. Panic? Terror? Despair? Again, her face is blurred, unreadable; whatever is going on here, we are left to guess.

Four decades since her death, the photographs made by the young American artist Francesca Woodman still feel like riddles. What are her hundreds of surviving prints – largely produced in the same small format, nearly all black and white – getting at, with their intense theatricality and gothic, ghoulish sensibility? Why did Woodman photograph herself again and again, posing nude in graveyards and abandoned houses or entwining her body with tree roots and rotting vegetation? Is this feminist performance, a tribute to classical art, or something less placeable altogether? And what clues do these images offer about the woman who made them?

Untitled, Florence, Italy, c 1976 (Credit: Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

That last question is especially fraught because, in January 1981, a few years after making these pictures, Woodman took her own life at the age of just 22. Her photographs had rarely been exhibited publicly, and a book she'd been working on hadn't yet been published; it was handed out at her funeral.

Perhaps inevitably, this has only added to the myth-making. In the decades since Woodman's work was rediscovered – it's now been exhibited in major museums worldwide – few critics have been able to resist using the circumstances of her death as the key to unlock her work. Society loves the idea of tormented artists, particularly young female ones. Even better if they happened to be neglected during their lifetimes. As an article in Slate once put it, "Is Francesca Woodman the Sylvia Plath of photography?" To which the only sane answer might be: what does that even mean?

A new exhibition at the Marian Goodman gallery in New York invites us to look again at Woodman, perhaps more carefully and attentively. Pointedly entitled Alternate Stories, it contains about 50 photographs and contact sheets, nearly half of which have never been seen publicly before. Revealing excerpts from her copious notes and writings are printed in the accompanying catalogue.

"It feels important to give Francesca her own voice," says Lissa McClure, head of the Woodman Family Foundation, which guards the photographer's legacy and is behind the new show. "It's about time."

A master image-maker

Woodman was born in Denver, Colorado to a family in which, according to her older brother Charles, art was a kind of religion. "It was like a background, just there," he tells BBC Culture over the phone, from his home in California. Their mother, Betty, made ceramics; their father, George, was a painter and taught at the university. Though money wasn't plentiful, Charles recalls family holidays in Europe during which the kids spent most of their time being dragged through museums and galleries, imbibing art.

"Oh, endlessly dragged," he laughs. "We kind of assumed that was normal – of course we'd been to the Sistine Chapel, of course we've been to the Prado, to the Louvre." (Charles, too, ended up as an artist, this time in video and electronics.)

Francesca's way in was the medium-format Yashica camera her father gave her when she went to boarding school in 1972. Encouraged by a teacher, she started taking pictures almost immediately and appears to have emerged, astonishingly, almost fully formed. One remarkable early work, Self-Portrait at 13, shows her in baggy fisherman's sweater and trousers, face swallowed by a mane of thick hair, caught in a halo of light (she appears to be operating the shutter-release with a stick or cable pulled taut, which becomes a ghostly presence in the frame). Even the title is an art-historical in-joke – a reference to a famous self-portrait made by the Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer at the same age.

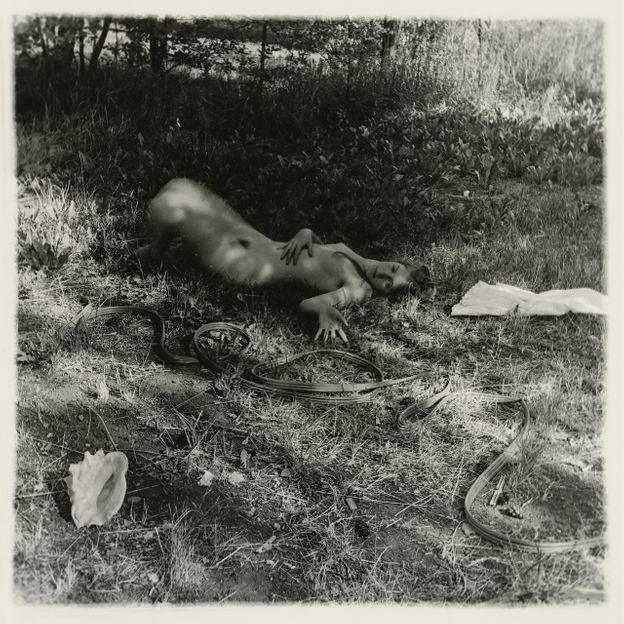

Untitled, Boulder, Colorado, c 1975 (Credit: Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Other early images pay homage to Romantic landscapes by Caspar David Friedrich or call to mind Victorian "spirit photography", in which photographers used all manner of tricks (blurring from slow shutter speeds, lens flare, double-exposures) to make it seem as if ghosts were being caught on film. It's also possible to see the imprint of surrealist photographers such as Dora Maar and Man Ray, as well as references to everyone from Edgar Allen Poe to Zola and Colette.

"She knew how to make a good photograph and she knew how to do that at a very young age," says McClure. "The sophistication of her images and the content are just so rich."

Perhaps the greatest influence on the young Woodman was Italy. She learned Italian when the family moved there for a time and returned to Rome in her study-abroad year from Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). As well as palling around with older artists – many of whom appeared a little overawed by her talents – she was heavily touched by classical architecture and allowed the city's intoxicating mix of beauty and decrepitude to seep into the silver-gelatin prints she was developing.

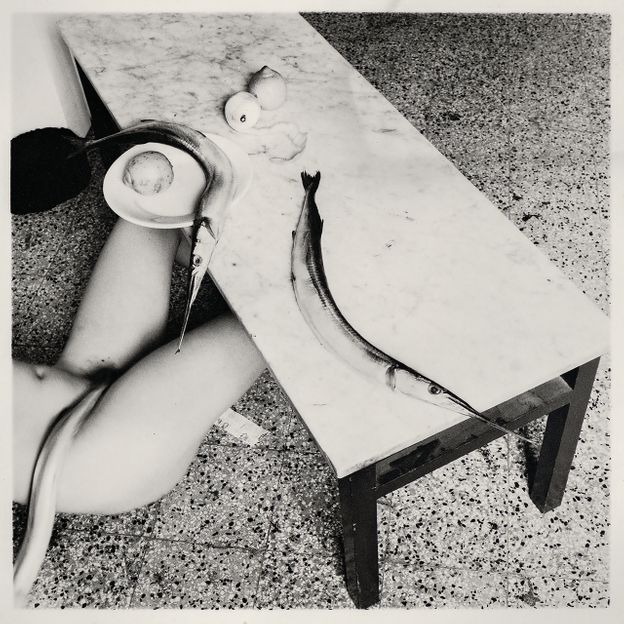

One project, Fish Calendar – 6 Days (1977-78), is a series of self-portraits-cum-still lives in which Woodman poses with what she described in her journal as "the most beautiful lemons clothed in soft green mould" and some sinister-looking, eel-like creatures she bought in a local market. One image shows her standing with only her legs in view, dangling a fish between her thighs so it merges with the curved stripes of her tights (the tights reappear in another picture taken around this time: Woodman had a great eye for clothes).

Untitled, Italy, 1977-1978 (Credit: Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

In another picture, she lies naked on the floor beneath the table, with a fish draped over her crotch and another pointing towards it. Powerfully strange, these images are also oddly erotic; somehow both suggestive, withholding and just-about funny (the stench was so bad, Woodman admitted, that she was forced to work in the basement). The strong sense is of a young woman fascinated by the shape of bodies in space, and the power of her own in particular. "After that time in Italy during college," says Charles Woodman, "she was already a professional artist."

Indeed, while Woodman's self-portraits look spontaneous, as if the artist is inviting us to witness her at her most intimate and vulnerable, in fact they were carefully choreographed and staged, argues curator Katarina Jenric. "She really went into her picture-making in a very deliberate way," Jenric suggests. "Each contact sheet that I've come across has at least a half a dozen frames trying to work out what the right composition should be for a particular photograph. Nothing is one-off. You really get the sense of her working through an idea."

In a note printed in the new catalogue, Woodman herself described her process as an opening-up of possibilities: "I feel that photographs can either document and record reality or they can offer images as an alternative to everyday life… places for the viewer to dream in." Dreamlike as so many of her images are, none of them came about by accident. Like a great theatre or film director, the artist knew exactly what she was doing, creating just the right balance between control and improvisational freedom.

Two untitled images, taken in Rome somewhere between 1977 and 78, offer a tantalising window into those possibilities. Both show her in what appears to be another artfully abandoned space, all distressed plaster and damp-stained walls. In one, Woodman, wearing a long black dress, holds herself by her long hair as if her whole body is dangling from it – a figure of mourning, perhaps, or entrapment. The next picture contains exactly the same elements (the two frames were likely shot only a few minutes apart) but couldn't be more different. This time she's mid-jump, a blur, with the hair sailing above her. Look how high I can go, she seems to say; look how free I am.

Untitled, Rome, Italy, 1977-1978 (Credit: Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

How exactly she shot these images, apparently working largely alone, remains mysterious. Simply from a technical point of view, Jenric points out, Woodman was a master of her photographic craft: able to manipulate illumination, shadow, composition and timing with uncanny precision. Through her studies with the respected photographer Aaron Siskind, she also had the darkroom skills to conjure remarkable visual effects from her negatives. "It's interesting to see how she really worked the images," Jenric says.

Somehow it's hard not to think of Emily Dickinson – stories half-told or images not-quite-revealed, the same sophistication and deliberation, the same sense that we're being invited in but also kept out of reach. Whatever Woodman's photographs evoke, in other words, it's not remotely straightforward – and if we take them at face value, we miss all the dedication and intention and fierce skill that went into creating them.

Their sly humour, too. By all accounts, Woodman was a charismatic and vivacious presence, and that makes itself felt in the pictures too: in one famous image, three young women (again nude) stand in a room, holding up prints of Woodman's face that block their own. The title Woodman gives the photograph is About Being My Model. Are any of these women the artist herself? Does it even matter, she seems to ask, playfully. Why are you all so interested?

Shadows and illusions

Where is her death in all this, we might ask. Is it visible at all? While Woodman had been experiencing periods of depression after returning to the US and moving to New York – not many galleries were interested in photography and she felt out of place in the art world – she continued to make work, often more abstract, and embarked on a project collaging her own images with an Italian school textbook (such is the craze for Woodman that copies now fetch $10,000-plus).

McClure argues that it's impossible to know if there's a connection between the elusive scenarios or roles she performed on film and what was happening for her emotionally – and equally unlikely there was just one truth to what was going on. "It's just kind of an impossible question to know what really happened," she says. "And I worry that having a conversation about [her death] takes away from the conversation being about her work."

Charles Woodman agrees that it's wrong to interpret her images as confessional testaments, still less as suicide notes: "It's not the lens I see it through," he says.

This feels important: in a documentary made decades later, a schoolfriend recalled that, in the weeks before Woodman's death, she stopped making pictures altogether – something she interpreted as a warning sign that, far from feeding Woodman's creativity, her depression was eating away at it.

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1978 (Credit: Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Her late images, taken between 1979 and 1980, show her moving in new directions, trying out colour film and creating a massive semi-abstract tableau, Blueprint for a Temple, in which she posed friends as architectural caryatids (column-like female forms), supporting a building she created from stitched-together images of a New York apartment.

It's tempting to think about which other kinds of image-making she would have become absorbed by; in which new directions she might have gone. But then, in a life lived at frantic high speed, perhaps Woodman had already achieved what she wanted to achieve. In the final journal entry written before her death, she refers to herself and her work in the past tense: "I was inventing a language for people to see the everyday things that I also see," she writes, "and show them something different."

For all the riddles and fugitive qualities of her work, she surely did that. Even if she were with us today, we would still be looking at and puzzling over these pictures. One of Francesca Woodman's greatest gifts is that she sensed the ultimate fact about photography: much as we may wish it to show reality, telling us things straight, of course it doesn't. As Woodman knew better than almost any artist, photography is a medium of shadow as well as light, of delusion and illusion and disappearance. We cannot know what sits outside the frame any more than we can know what happens before or after the shutter snaps open then shut.

"Photography supposedly captures the truth, and we all know that that's not possible," McClure says. "It only fixes a moment."

All images by Francesca Woodman

Leave a comment