Kelly Grovier from BBC picks 15 of the most startling photos from this year – including images of the riots at the US Capitol and an airplane in Kabul – and compares them with iconic artworks

(Credit: Reuters)

COP26 speech, Tuvalu, November 2021

Addressing the UN climate conference in Glasgow, the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu's foreign minister Simon Kofe stood in a suit at a lectern thigh-deep in seawater to demonstrate how rising sea levels and the accelerating climate crisis threaten his low-lying nation. "We will not stand idly by," Kofe insisted, "as the water rises around us." The striking image and his anxious words called to mind a whole history of images of figures and communities imperilled by the whim of waves and water, from Jan Asselijn's terrifying painting The Breach of the Saint Anthony's Dike near Amsterdam (which reconstructs the catastrophic tide that struck the Dutch coast in the wee hours of 5 March 1651) to German digital artist Kota Ezawa's 2011 computer-generated work The Flood, inspired by media images of high water sinking neighbourhoods in the deep south of America.

(Credit: Alamy)

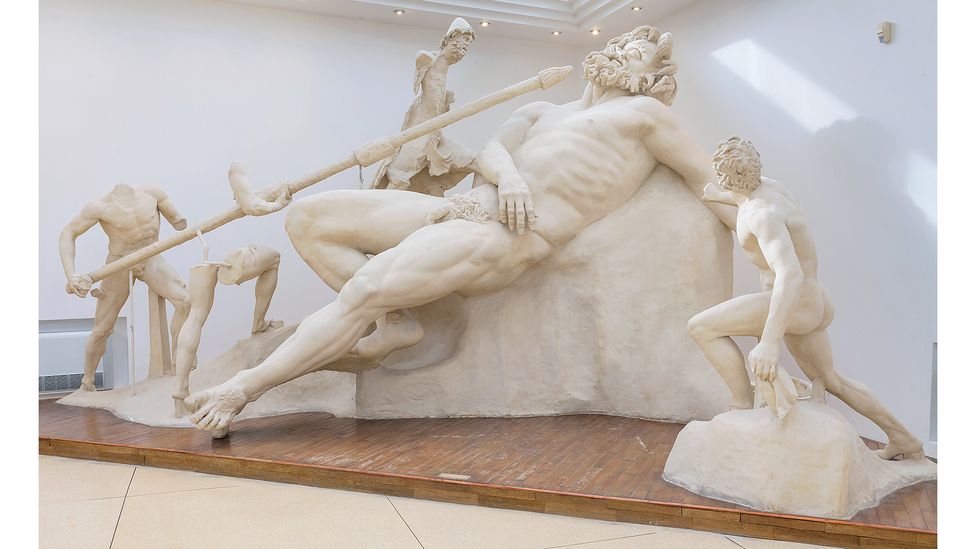

Sculpture, Italy, 2021

A witty photo allegedly depicting the invention of the lateral flow test went viral on social media in November. The cast reconstruction of a group of sculptures from the 1st-Century villa of Tiberius in Sperlonga, Italy, needless to say portrays something very different from present-day Covid swabbing: the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemus, who had trapped Odysseus and his party in a cave. According to the legend, Odysseus eventually manages to ply Polyphemus (who had eaten several pairs of the epic hero's entourage) with "undiluted" wine before lancing his single eye with a sharpened spear. Anyone who has self-administered the lateral flow test and accidentally probed a little deeper than they'd intended may feel Polyphemus got off lightly.

(Credit: Alamy)

US Air Force plane, Kabul airport, August 2021

When the Taliban entered the Afghan capital, Kabul, on 15 August, a US Air Force plane, bound for Qatar, became the last hope for evacuation from the city for many Afghans. Photos of hundreds of desperate people flooding the ramp of the C-17 Globemaster III plane were among the most dramatic captured this year. The unfathomable crush (estimated to have been between 640 and 830 adults and children) managed to make the claustrophobic vision of contemporary Canadian artist Timothy Schmalz's recent sculpture Angels Unawares – a 20-foot-tall bronze boat crammed with displaced souls – seem commodious by comparison. Unveiled by Pope Francis in September 2019 on the Vatican's World Day of Migrants and Refugees, the work takes its name from a moral instruction in the Epistle to the Hebrews: "Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares."

(Credit: Getty Images)

Astronauts, Israel, 2021

A pair of astronauts stride side-by-side in spacesuits during a training mission for Mars at the Ramon Crater in Israel's Negev desert. The world's largest "makhtesh" (a type of erosion depression that is not formed by the impact of a meteor or the eruption of a volcano), the heart-shaped canyon served as the surreal retreat for six astronauts from Austria, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. The crew was only allowed to explore the desolate terrain in spacesuits, to approximate conditions they'll face on Mars. Photos of the alien simulation captured the world's imagination and appeared to portray not so much a physical realm in our own solar system than a lonely and luminous soulscape – a metaphysical elsewhere like those imagined by the French avant-garde artist Yves Tanguy…

(Credit: Getty Images)

Protesters, Scotland, November 2021

During the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November, activists from the Ocean Rebellion group demonstrated outside the INEOS integrated refinery and petrochemicals centre plant in Grangemouth, Scotland. Self-dubbed "Oil Heads", for their use of plastic petrol jugs as grotesque masks, the campaigners dramatically spat oil and flung fake cash to lampoon the behaviour of investors and politicians who, they contend, are acting too slowly in their pledge to end deforestation by 2030. The crude image is viscerally effective, and calls to mind a notable leitmotif in works of contemporary art by artists calling attention to the deleterious impact on the environment caused by man, a tradition that stretches from the late Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi's Oil Pool (a long-running series that began in the 1970s) to Ai Weiwei's more recent Oil Spills, 2006.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Diver, China, January 2021

In January, a woman was photographed diving from a plinth of ice rising from a frigid lake in Shenyang, in northeastern China's Liaoning province. Frozen above the bitter water's glassy surface, she remains forever suspensefully suspended – neither part of time nor outside it, weightless nor heavy. The heroic horizontality of her body rhymes with the measured stretch of snowy path or bank that splits the photo into equal parts earth and air. To the eyes of many, the severity of the environment and discomfort that eternally awaits the swimmer makes her pendulous plunge as inconceivable as swan-diving towards a street from an urban ledge – a feat the French artist Yves Klein claimed he did from a Parisian window in 1960. Recreating the toe-curling lunge, Klein hired a couple of photographers to help him stage a series of images he called "Leap into the Void", which capture a body stretched out mid-air in a posture very similar to that of the Chinese diver.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Girl, Gaza, May 2021

In the bloodiest escalation of conflict between Israel and the Palestinians since 2014, air strikes unleashed by the former (in retaliation for a rocket fired from Hamas) ripped open the home of a little girl in Beit Hanoun, Gaza on 24 May. The image of the girl – standing barefoot amongst rebar and rubble, gazing at her shattered horizon – is heart-breaking. The incongruity in such a scene of a stuffed bunny, who stares upside-down at the upside-down world, brought to mind British artist Paula Rego's 2003 painting, War, which is itself based on a media photograph of a young girl, taken during the traumas of the Iraq war. In Rego's raw vision, the rabbit – conventionally a symbol of innocence and rebirth in art history – is poignantly recast as a menacing mask of anguish. In the image from Gaza, no reinterpretation of the horror is necessary.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Lake, Serbia, 2021

The photo of a grotesque glacier of garbage clogging the Lim river near the city of Priboj in the Western Balkans, is breathtakingly grim. A convergence of relaxed waste management measures, an escalation in illegal dumping, and floods in the region – which helped carry the rubbish to a single spot – was to blame. The incongruity of the dense debris in an otherwise pristine landscape calls to mind the unsettling vision of the contemporary Cuban artist Tomás Sánchez, who reimagined the site of Christ's crucifixion outside Jerusalem in his 1994 painting Al sur del Calvario (South of Calvary). A muckscape of unrecycled trash, Sánchez's painting suggests salvation is as much a material slog through worldly sludge as it is an arduous spiritual journey.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Boy, Indonesia, 2021

An eight-year-old boy begs on the streets of Depok, Indonesia. His skin is covered in a toxic concoction of metallic paint and cooking oil that transforms his body into a kind of burnished sculpture. Aldi is among a group of people known as Manusia Silver (or "Silver Men") who resort to this dangerous disguise in order to attract alms. The image of Aldi, glimmering amid the steely ooze of traffic on a congested city street, is especially affecting. For many boys Aldi's age, robots are talismans of wonder – a theme that invigorates Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi's ink-and-gouache enhanced photograph Wonder Boy, 1971, which imagines a boy merging with the magic of his toy robot. In Paolozzi's photo, the two dissolve into the same shimmery substance. The image of Aldi, however, tragically subverts that childlike instinct to lose oneself in play.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Capitol riot, US, January 2021

Photos of supporters of Donald Trump violently clashing with Capitol Police in the Rotunda of the US Capitol on 6 January shocked the world. The pro-Trump trespassers were protesting the certification of Joe Biden as President-elect. It may come as a surprise to some that the image of Americans at each others' throats is part of the very fabric of the space. Outside the frame of this photo, behind the cameraman who took it, a sandstone relief sculpture by the 18th-Century Italian sculptor Enrico Causici depicts the colonising frontiersman Daniel Boone locked in hand-to-hand combat with a Native American. The crumpled body of another lies beneath their feet. The merits of the work – aesthetic and moral – are as likely to provoke polarising opinion these days as the events of 6 January.

(Credit: Alamy)

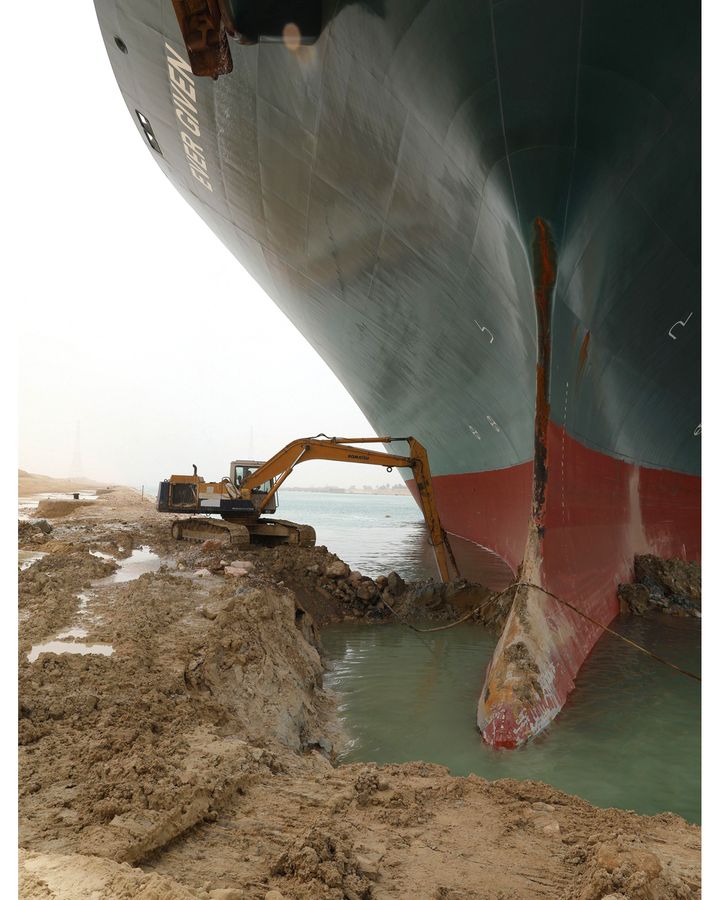

Ever Given container ship, Egypt, March 2021

When a colossal cargo ship jammed itself sideways in Egypt's Suez Canal in spring 2021, the world, like global shipping traffic itself, suddenly stopped in its tracks. Travelling from China to the Netherlands, the Ever Given ship had been lugging 20,000 shipping containers when it wedged whopper-jawed near the southern end of the canal early on 23 March. With its stern stuck against the western wall and its bow buried deep in the sandy eastern side, the ginormous ship wasn't going anywhere. Photos of a diminutive digger attempting to free the vast vehicle inspired many a mirthful meme and brought to mind famous farcical images of miniature muscle determined, David-v-Goliath style, to defeat a mammoth problem, such as a 15th-Century tempera-and-gold illustration from a Book of Hours by the anonymous Flemish illuminator known as "The Master of the Dresden Prayer Book".

(Credit: Environmental Photographer of the Year 2021)

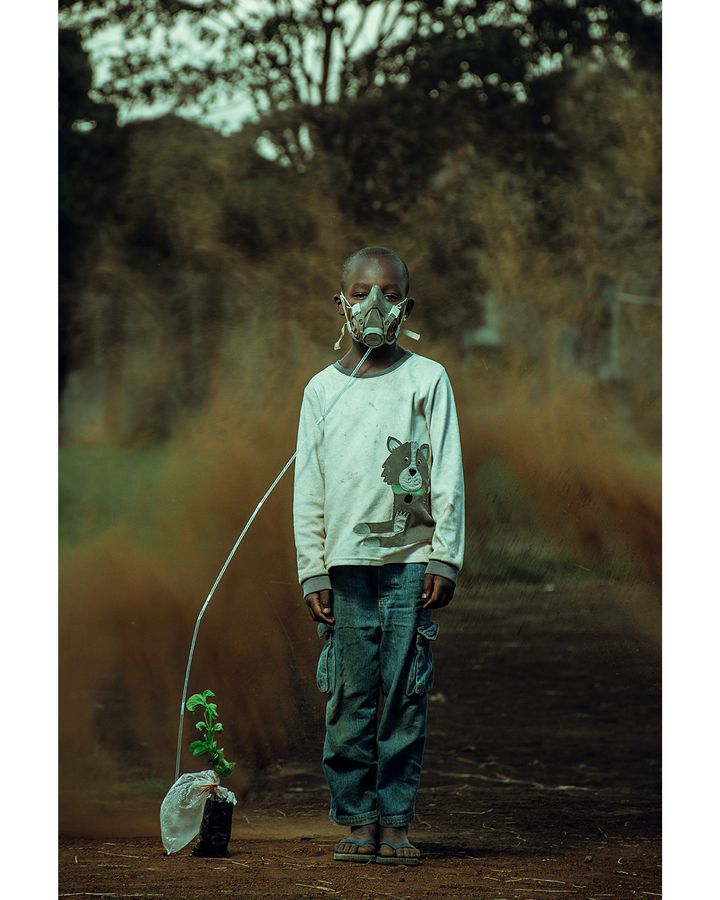

Boy, Kenya, 2021

In November, the winners of the Environmental Photographer of the Year 2021 were revealed. In the Climate Action category, a photo of a young boy attached surreally, via face mask and respirator, to a potted plant standing beside him like an oxygen tank, prevailed. A powerful meditation on the trajectory of environmental damage, The Last Breath by Kevin Ochieng Onyango was photographed in Nairobi, Kenya. The image not only looks forward into our uncertain future but back into art history, absorbing and subverting influential works from the past. The fragility and preciousness of breath recalls themes that invigorate such works as Joseph Wright of Derby's 18th-Century masterpiece Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump (informed by the recent discovery of oxygen by Joseph Priestley) and Italian artist Piero Manzoni's conceptual work from 1960, Artist's Breath, for which Manzoni attempted to preserve forever his breath in a red balloon. The friction between Manzoni's intention for the work ("When I blow up a balloon," he once insisted, "I am breathing my soul into an object that becomes eternal") and the eventual fate of his balloons – which have long since deflated and decomposed – speaks, however breathlessly, to the poignancy of Onyango's haunting image.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Painting, France, October 2021

The photo of French firefighters raising a fireproof blanket to protect one of the many treasures in the Saint-Andre cathedral during a drill in Bordeaux, France, in October, was itself a work of art. The painting at the heart of the image was created by the 17th-Century Flemish master Jacob Jordaens and depicts an agonisingly crucified Christ jabbed by long skewers fitted with vinegar-soaked sponges, against a thickening gloom. The ladders that flank the canvas align themselves with tropes of ascent and descent depicted in the painting, and transform the work into something curiously kinetic – a vision that is neither wholly real nor imagined, spiritual nor quotidian. The leaning props connect us to the past and incline our imagination to the many-runged tradition of works whose levels of meaning are measured along the angled length of rising ladders, from the so-called Ladder of Divine Ascent (a late 12th-Century icon in Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai), which portrays monks climbing towards Jesus, to the French-American contemporary artist Louise Bourgeois's series of drawings The Ladders, through which she constructs a characteristically ambiguous personal symbol – at once precarious and uplifting.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Children, Ethiopia, July 2021

In July a group of children were photographed standing under a tree on the site of a future camp for Eritrean refugees, near the village of Dabat, northeast of the city of Gondar, Ethiopia. A threadbare scarf of mist enveloping the scene gave the image a mythic quality. The living shelter provided by the lyrical canopy of leaves and the imagined music of its stationary rustle brought to mind myriad examples in cultural history of Trees of Life – a theme that has inspired everyone from the ancient Uratrians, for whom the tree figured as an important religious emblem, to the Viennese Art Nouveau artist Gustav Klimt, who winds the branches of his poetic Tree of Life into symbolic spirals – coils of a spiritual engine that whirr into eternity.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Health workers, India, October 2021

To mark the administration in India of the one billionth dose of vaccine against the coronavirus, four members of the nursing staff at the Ramaiah Hospital in Bangalore posed in October for a photograph in the guise of the widely-revered Goddess Durga (associated with strength and protection), who is typically depicted with many arms, each wielding a weapon with which she skilfully defeats her enemies. It is not the first time that Durga, a major Hindu deity credited with combating evil forces, has been invoked during the pandemic. A year earlier, in October 2020, images of a six-foot sculpture of Durga, which the Indian artist Sanjib Basak had fashioned from discarded injection vials and the blister packs of out-of-date medicine strips, went viral on social media. Emerging from a heap of hospital waste – the detritus of discomfort and disease – Basak's sculpture sounded an unexpectedly hopeful note in the face of anguish and adversity.

Leave a comment