Heidi Allen, Anna Soubry and Sarah Wollaston are not the first MPs to break away from the Conservative party. The list of Tory resigners goes back to Winston Churchill in 1904 and beyond. And they are unlikely to be the last. Back in October I had a coffee at the Tory conference with a cabinet minister who confessed: “Part of me is longing for Boris Johnson or Jacob Rees-Mogg to become leader so the rest of us can just leave and join a new party.”

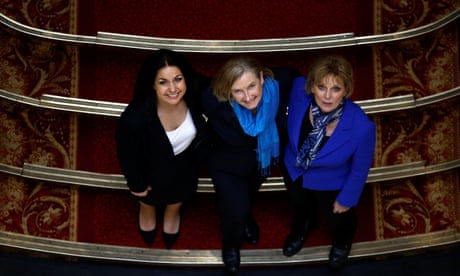

Wednesday’s departure of “the three amigos”, as Allen called them at their press conference, does not make that much larger Tory fissure a certainty – much will depend on the Brexit endgame. But it makes it more likely. It also marks a potential watershed for the 21st-century Conservative party. When the three former Tory female MPs - and their gender is definitely part of the story -crossed the floor of the House of Commons this morning, they threw down the gauntlet to an entire generation of 21st-century Tory modernisers to either stand up or stand down.

They did something else too. The sight of a group of MPs abandoning a Tory government to sit with the opposition is unusual enough. What made their move even more unusual was that the three women went straight over to sit with the seven – now eight – former Labour MPs who themselves broke with Jeremy Corbyn’s party on Monday. By doing this they raised, in the most visible way, the possibility that these 11 independents are the outriders of a new party formed from simultaneous splits of both the two main parties in parliament.

Commentators should be wary of claiming that things are without precedent. But it is genuinely hard to think of any previous new political grouping that drew on both the main parties as this one has. That was certainly not the case with the Social Democrats in 1981, who were overwhelmingly a split from Labour. Let’s just agree that British party politics has witnessed something extremely unusual this week, whether it succeeds or it fails.

It is tempting to see the independents as the often trailed new centre party that many have expected – and some have hoped – would emerge from the simultaneous moves of Labour to the far left under Corbyn and of the Tories to the far right in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. Some of the independents see themselves that way. Sarah Wollaston was explicit that her move was “about more than Brexit”, and that she foresaw a “third way” grouping. The independents’ website also says they aim to provide a home for refugees from both parties.

Much of the commentary on this week’s events will present the independents in that light. There is some truth in it. The independents have a social market ideology that slots between the extremes on the old left-right spectrum which some still use to explain our politics. They think of themselves as centrists of both the left and right. The polls show a section of the electorate – as much as 10% in the first week of their existence – has quickly embraced the new grouping.

The independents would not exist except for the politics of Brexit. Frustration with Corbyn’s equivocations on Brexit helped to drive the former Labour MPs into the group. Despair with the Tory right’s grip on May’s Brexit strategy did the equivalent for the former Conservatives. Yet on Europe, as the political scientist guru John Curtice argued today, “There is simply no centre ground.”

Britain is split down the middle on the Brexit issue. A centrist position might arguably be to accept a soft Brexit. Yet the independents are not selling themselves as soft Brexiters but as solid remainers and advocates of the so-called people’s vote. They want a second referendum in the hope that it will overturn the first. “What is remotely centrist about this exercise?” Curtice asks about the new grouping. “On Brexit they aren’t centrists; they are extremists.”

This is neither a value judgment nor a trivial point. It is simply the case. Brexit has never sat neatly on the left-right spectrum. Most people on the left are remainers, but a significant minority aren’t. Most on the right are leavers, but plenty are not. But the left-right spectrum is not the only spectrum that matters in modern politics. Curtice argues that the axis running from social-liberal to social-conservative is just as important nowadays. Brexit fits in more predictably there. Social liberals tend to be remainers while social conservatives are mostly leavers. In Scotland, there is also a third spectrum to take account of, in the shape of the national question.

Seen in that light, the defining thing about the independents is therefore not that they are centrists. It is that, as remainers, they are social liberals. But that in turn means two things. First, they stand for something that alienates socially conservative voters. Second, they are not seeking to fill a large gap in the market – as they tend to claim when portraying themselves as centrists – but are competing with other existing socially liberal parties for votes. The most obvious such party is the Liberal Democrats, and the new grouping will have to decide whether they regard Vince Cable’s party as part of the answer or part of the problem. Similar decisions will be needed in relation to the Greens and the Scottish and Welsh nationalist parties.

But the biggest challenge for the independents is to evolve an agenda for Labour voters. In 2017, Corbyn captured very large swaths of the pro-remain, socially liberal, university-educated parts of the electorate who don’t vote Lib Dem, Green or nationalist. These are precisely the people at whom the independents are aiming. But Corbyn is a leaver, not a remainer. He wants Brexit to happen. His hold on those voters is therefore at risk.

That gives the independents a clear chance, especially if Theresa May’s efforts to patch up her deal with the EU fall apart. Labour has millions of remain voters. Some Tory voters will be open to that appeal too. But the independents cannot assume that Labour remainers are all centrists in the old Blairite sense of the 1990s. The centre of gravity on the left-right axis is never stable. It must be constantly redefined in the light of changing times. And the centre has shifted a lot, as it always does. Attitudes towards nationalisation, for instance, have shifted to the left.

This is the real challenge to the independents. They have learned the hard way that the existing party system no longer articulates the divisions and aspirations of the electorate. They know what is wrong. They have made a bold break. Now they must say what they will put in its place. They may not have long. This week’s churning means an early general election just got a bit more likely.

The Guardian

Leave a comment