At the point when Miles Davis visited the UK in the harvest time of 1960, there was no huge ballyhoo about his as of late discharged collection Kind of Blue. The trumpeter played presently lost scenes, for example, the Gaumont Palace films in Kilburn and Lewisham, London – beginning and completion his sets with melodies from the collection – and at the time, he told a companion of my father's, an advertiser called Jim Ireland who was taking care of parts of his visit, that he expected to profit from Kind of Blue.

Sixty years on, the collection is hailed as an artful culmination of current music. It is the top of the line jazz record ever, having sold about 5 million duplicates and been guaranteed fourfold platinum. It was No 1 on the BBC's 50 biggest jazz collections survey in 2016, No 12 on Rolling Stone magazine's rundown of the 50 biggest collections ever and even, strangely, highlighted in VH1's "100 Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Albums".

Sort of Blue's 46 minutes of spontaneous creation and five star musicianship still pulls in aficionados all things considered. Jazz performer Courtney Pine said it was "the record I'm proudest to claim"; Quincy Jones called it "my every day squeezed orange"; Steely Dan's Donald Fagen depicted it as "the Bible" of music. Pink Floyd piano player Richard Wright said the collection affected the entire structure of The Dark Side of the Moon.

Music from Kind of Blue has highlighted in various famous TV arrangement, including The Wire, Dexter, Better Call Saul, True Blood, Mad Men, The Simpsons, Homeland, The West Wing and The Marvelous Mrs Maisel. On-screen character Judy Dench says that "the heavenly" track "Blue in Green" is one of her most loved bits of music. "I knew Miles Davis in New York, and the minute I hear Kind of Blue, I return in one of those awesome smoky rooms in New York," the Oscar-champ revealed to Desert Island Discs.In an important scene in the motion picture Pleasantville, in which Tobey Maguire and Reese Witherspoon's characters are transported back to the high contrast 1950s universe of an anecdotal network show, Kind of Blue is playing out of sight. Less amazingly, Davis' collection is additionally the ringtone on the cell phone of previous Tory MP Eric Pickles.

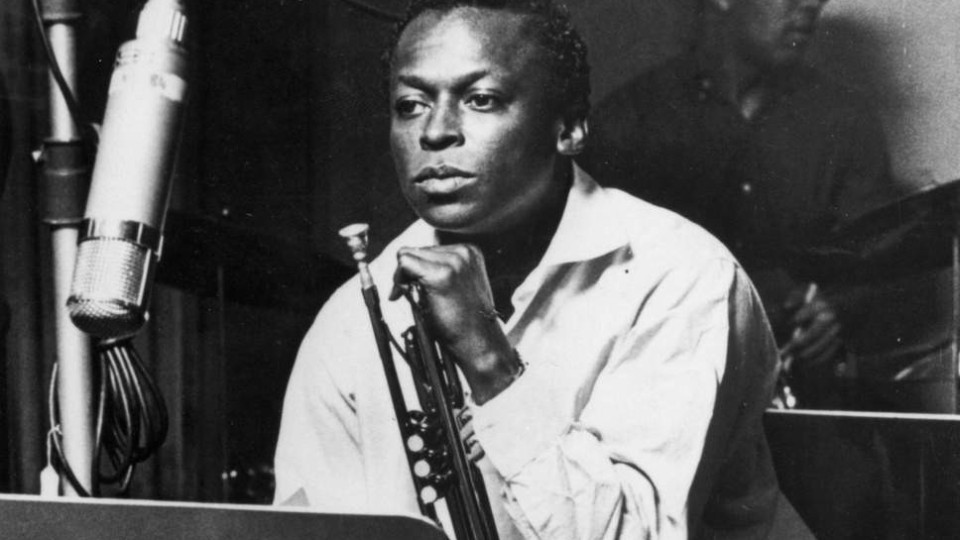

Sixty years back, as he was going to make a quantum jump in music, the notoriety of trumpeter and arranger Davis was discolored. He was 32, still meager in the wake of recuperating from a dependence on heroin, and broadly viewed as temperamental. Musically, he was stressed over being dominated by more youthful adversary Chet Baker, who had as of late won the DownBeat pundits survey for "best trumpet player". Regardless of this, the man Duke Ellington named "the Picasso of jazz" realized he included it inside him to make something as pivotal as Kind of Blue.

At 2.30pm on Monday 2 March 1959, Davis gathered a heavenly band at East 30th Street in New York, the site of Columbia's account studio. It was in a changed over Greek Orthodox Church, one in this way annihilated to clear a path for elitist pads. Aside from Davis himself, who plays remarkably well on the collection, Kind of Blue highlights John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on alto saxophone, Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly on piano, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb – every single sublime entertainer at the tallness of their forces. Dissimilar to numerous supergroup sessions, this was generally a working band and they were loose in one another's melodic organization. To them, it was simply one more independent booking.

The band were given portrayals of the initial three tunes, two of which Davis had been taking a shot at that morning. They had never recently played the organizations. "While I was setting up the drums, I was reasoning, 'I wonder what we are going to play today?'" Cobb said in 2009. "The tunes were simply something Miles had on an error of original copy paper. The folks needed to truly work to manufacture something from that smidgen."

The trumpeter, who is the subject of the inevitable film Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool, said the familiarity was purposeful. "On the off chance that you put a performer in a spot where he needs to accomplish something else from what he does all the time ... that is the place extraordinary workmanship and music occurs," he wrote in his 1989 collection of memoirs.

Davis needed to catch the artists' unadulterated immediacy. In the first liner notes, piano player Evans said the performers were willing "to twist for the outcome" and adapt to his testing interest for "amass act of spontaneity". Evans, whose flawlessly downplayed piano playing sets a great part of the melodic tone of Kind of Blue, composed a note to Adderley as they were playing "Flamenco Sketches" encouraging him to "play in the sound of the scale". Adderley obliged with some eerie impromptu "blue notes".

The collection's purported "modular jazz" – impromptu creation dependent on scales as opposed to a harmony movement got from the blues or a prominent tune – was progressive. Herbie Hancock says that even proficient artists wonder about the manner in which Davis and co ad libbed inside the sound and structure of the organizations and moved into "a new strange area". Chick Corea was likewise dumbfounded by the collection. "It is one thing to play a tune or a program of music, yet it's another to for all intents and purposes make another dialect of music, which is the thing that Kind of Blue did," said the piano player. Quincy Jones went similarly as calling it "a masterpiece that clarifies what jazz is".

Cobb said that a large portion of five tracks – "So What", "Freddie Freeloader", "Blue in Green", "All Blues" and "Flamenco Sketches" – were fixed in one take. "That is the thing that Miles enjoyed," included Cobb. "In the event that you continue doing it over, it gets the opportunity to be stale. He figured your first shot is your absolute best." The off the cuff idea of the sessions is clear from transcripts of the ace tapes. Similarly as "Blue in Green" is going to be recorded, Davis says to Coltrane: "For what reason don't you play on this?". His imaginative saxophone-playing changes the ballad.By 1959, swings groups were in decay and bebop was start to change the essence of jazz. "Out of the blue, everyone appeared to need outrage, coolness, hipness and genuine spotless, mean advancement," said Davis. Cobb trusts that piece of the intrigue of Kind of Blue was that "it was not quite the same as what was happening at the time ... show tunes or prevalent tunes, with a great deal of harmony changes and stuff that way. This was only a sort of curbed, simple listening sort of stuff that you didn't need to be truly saturated with the music to appreciate."

Cobb said Davis was a stickler. The trumpeter would lean in near a non-soloing artist to murmur directions in his ear amid a take. On the off chance that he didn't care for how a practice was going, he would call an end by blowing a whistle, an instrument he utilized as opposed to yelling directions, following changeless harm to his vocal lines caused four years before amid a yelling match with a club director.

The sessions for Kind of Blue were not tense undertakings, in any case. There was the typical artist talk. At a certain point, Davis gripes to co-maker Irving Townsend about the commotion from the squeaky floor, at a studio picked for the regular acoustic reverberation of the high roofs. Previous teacher Adderley answered that he ought not stress over the "surface commotion", before Evans tolled in with a brisk play on words, asking Davis for what valid reason he didn't care for the "surf-ass clamor".

Fred Plaut, the designer at the sessions, more often than not dealt with traditional music chronicles and was exact about the area of the four-recording devices he kept running in synchronization for a collection recorded in mono and stereo (a typical practice at the time). Lamentably, the mono tapes were lost during the 1960s, apparently until the end of time. The first Side A squeezing was issued at the wrong speed (a blame in one of the recording devices had been remedied constantly session in April), at a pitch that was a quarter-tone excessively sharp. These defects were adjusted when the collections were remastered and re-discharged during the 1990s. Furthermore, the principal collection sleeve bore wrong track postings.

In spite of these specialized flaws, Kind of Blue was discharged on 15 August, as a 12-inch vinyl record, to prompt praise. "This is an amazing collection," said DownBeat, giving it a most extreme five-star rating. "Utilizing basic yet successful gadgets, Miles has made a collection of extraordinary magnificence and affectability ... this is the spirit of Miles Davis and it is a wonderful soul."

Sort of Blue was all the while selling in huge amounts a couple of years after its discharge and it was at exactly that point, Cobb stated, that the performers started to acknowledge they had made "something uncommon". The drummer was resolute that none of them had the smallest thought in 1959 that they were making jazz history. "That never came up. It was simply one more incredible Miles Davis recording that everyone played well on," included Cobb. "In the event that Miles even had a suspicion that that was going on he would have requested a truckload of cash and four Ferraris sitting outside. That is the manner in which he contemplated things."

It is a calming imagined that the skilled artists passed up a decent amount of the benefits from this multimillion-selling treasure. Ashley Kahn, the creator of Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece, was once asked what the sidemen earned from this worldwide hit. "Miles' sidemen made generally $130 for the two sessions joined. In any case, another reminder uncovers that Miles demanded – fairly uniquely – that the three senior individuals from his gathering [Coltrane, Cannonball and Chambers] get an extra $100 each. After somewhat forward and backward between different divisions at Columbia Records, the checks were cut. Last sum paid to Coltrane, Cannonball and Chambers: under $250 each. Evans and Cobb: under $150 each. Wynton Kelly, who performed just on the principal session: under $75."

Leave a comment