Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing review – the superhuman hits you like a thunderbolt

5/5stars5 out of 5 stars.

Museums across the UK

These drawings from the Royal Collection – dispersed around Britain – are like pure, clear windows on to the extraordinary mind of this enigmatic and visionary genius

It was in Cardiff that I finally cracked the Da Vinci Code. For years I’ve been searching for the clues that would explain this weird and wonderful genius. I’ve visited the Tuscan hill town Vinci, where an illegitimate boy called Leonardo was born in 1452, and Amboise in the Loire Valley, where he died on 2 May 1519, looking for traces of his secret self. Yet it was on an icy afternoon in the Welsh capital that I finally found the killer clue to a real Leonardo da Vinci mystery: his sex life.

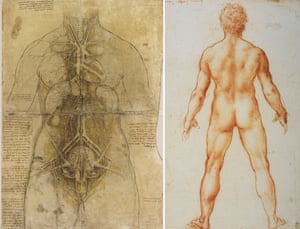

Leonardo’s inky fingerprint has been found – it’s just barely visible with the naked eye – on his drawing The Cardiovascular System and Principal Organs of a Woman, done c.1509-10, yet this is not the revelation. This big, bold graphic dissection of a female body is a window on Leonardo’s emotions. He has drawn a female nude then transposed against her rounded breasts a complex machinery of tubes and pumps, bags and balloons. Her uterus looks like an alien creature. As an image of the female form it isn’t exactly intimate, let alone lustful. At the National Museum Wales, you can look straight from this to a far more sensual portrayal of the human body that he drew in about 1504: a scintillating study of a naked man from behind. Leonardo’s muscular model stands at attention, showing us his curly locks and rippling back. His hands seem to visibly shake with contained energy. His stance is potent. Leonardo uses red chalk to give this nude a carnal warmth: its softness lets him delicately model every bulge and recess of taut skin. The man’s buttocks are ripe ovals of perfection.

These drawings shown together truly seem to decode something about the Renaissance artist, scientist, engineer and inventor who died 500 years ago this year. To celebrate Leonardo’s half-millennium, the Royal Collection, which owns the world’s most eye-popping hoard of his graphic works, has scattered traces of his true self across the UK: 12 museums in 12 cities have each got a piece of him. Perhaps, if you could somehow see all the shows, you would know everything there is to know about Leonardo. He would come to life and talk.

And there is so much to explain. Looking from Leonardo’s loving, lingering male nude to his vision of what is clearly, for him, the alien entity of womanhood, it’s hard not to share Sigmund Freud’s analysis in his book on him that this Renaissance man loved other men.

Was Leonardo gay – and is that the key to his inner life? It's a marvel that we can even talk about him in this way

So is that it? Was Leonardo gay – and is that the key to his inner life?

And yet, before you can humanise Leonardo you have to acknowledge the superhuman in him. It hits like a thunderbolt in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery’s gorgeous show of drawings sharply lit against dark blue walls. Every drawing in this exhibition is more than five centuries old. And these medieval masterpieces are incredibly well preserved. Each nuance of chalk, ink and colour wash seems to have been frozen forever. This is one reason why, I believe, you can get much closer to Leonardo in his drawings than in his paintings. His paintings have been restored and repainted over the centuries, or fallen to bits, like The Last Supper. But these sketches are pristine. They are not by his assistants. They are pure clear windows on his mind, many with his notes in his reversed handwriting interspersed among the images.

In his drawing of A Storm Over a Valley he uses red chalk again, this time to create what feels more like a modelling of the atmosphere than a mere landscape sketch. Rolling banks of cloud billow above a mountain valley, releasing heavy cascades of rain on the settlements below. But what’s spooky is the point of view. Leonardo seems to be looking down on the little human world of churches and farms from far, far above.

Perhaps he’s standing on a mountaintop – he did explore the Alps. Yet there are other landscapes by him that also seem to be seen from the sky. Famously, he tried to make a flying machine. This drawing shows flight is central to his way of thinking about the world: he literally wanted to rise above it all.

Near the end of his life, he became obsessed with deluges tearing the world apart, smashing a mountain, destroying an army like ants

For Leonardo was not at ease in human society. Why would he be? In one drawing in the Cardiff exhibition he portrays a thuggish face, a huge, fleshy head on a thick neck. In another work, in Bristol, he delineates a savage battle. They are both instances of his bleak feelings about the brutality and violence of our species. Other masterpieces show how, near the end of his life, he became obsessed with deluges tearing the world apart, smashing a mountain, destroying an army like ants under the swirling power of the elements.

His curiosity is so insistent, like that of a staring child. Or maybe a serial killer, meticulously drawing the bones of the dead. No one had ever before looked at human anatomy as Leonardo does in drawings based on his own dissections. He finds within us a mysterious architecture. The interior of the heart is laced with fan vaulting like a gothic cathedral. Our bodies are labyrinths of tunnels and cavities, spheres and tree branches.

That magic weave of fragile organic stuff links all nature. In his portrait of a woman looking downward, a design for his late painting The Virgin and St Anne, she sports a richly textured lacy headdress. The ruffled silk looks like a jellyfish sac he’s seen washed up on shore: the Virgin is wearing a marine organism in her hair. In a map of the river Arno in Tuscany the blue tendrils of the river look like tentacles, roots, or veins in a human body.

The more of these drawings you see the more startling and real Leonardo becomes. But so does his jaundiced view of our species. We’re just part of a bigger picture. Human organs and the Earth, microcosm and macrocosm, all mirror each other. Perhaps that’s why the art of Leonardo leaves you so enraptured. I felt as if I could see my own skeleton and those of Cardiff passersby as I popped into Greggs for a vegan sausage roll. Come to think of it, Leonardo would have approved. He was a vegetarian. If everything is one interwoven fabric, he thought, who are we to act like lords of creation?

• Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing runs 1 February-6 May in in Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Derby, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Southampton and Sunderland. Then at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 24 May – 13 October.

As 2019 begins…

… we’re asking readers to make a new year contribution in support of The Guardian’s independent journalism. More people are reading and supporting our independent, investigative reporting than ever before. And unlike many news organisations, we have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford. But this is only possible thanks to voluntary support from our readers – something we have to maintain and build on for every year to come.

Readers’ support powers The Guardian, giving our reporting impact and safeguarding our essential editorial independence. This means the responsibility of protecting independent journalism is shared, enabling us all to feel empowered to bring about real change in the world. Your support gives Guardian journalists the time, space and freedom to report with tenacity and rigor, to shed light where others won’t. It emboldens us to challenge authority and question the status quo. And by keeping all of our journalism free and open to all, we can foster inclusivity, diversity, make space for debate, inspire conversation – so more people, across the world, have access to accurate information with integrity at its heart. Every contribution we receive from readers like you, big or small, enables us to keep working as we do.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

Please make a new year contribution today to help us deliver the independent journalism the world needs for 2019 and beyond.

The Guardian

Leave a comment