On the eve of a surprise Oxford show, the artist gives us a tour of his vast studio – and talks about inflatable metaphors and the controversy over his giant tulips

‘To get great clarity in the balls, you really need to blow them a lot,” says Jeff Koons, with all the solemnity of a man explaining his tax returns. He gazes lovingly at his balls, which in this particular case are a row of stainless steel spheres suitably blown up to bear an astonishing resemblance to his most famous artistic muse: inflatable rubber toys. But given that Koons shot to notoriety with his 1991 series Made in Heaven – in which he photographed himself and his then girlfriend Ilona Staller in pretty much every sexual position legal in the state of New York – this ball chat really could have gone another way.

Koons, who looks like Pee Wee Herman and talks like Mister Rogers, is taking me around his 10,000 square foot studio in Chelsea, New York. And if you think that sounds big, wait until you hear about his house: he, his wife Justine and their six children (Koons also has two older children from previous relationships) are about to move into their new fixer-upper, which is almost an entire block on the Upper East Side. Koons bought two mega mansions for a total of $35m and spent almost another $5m knocking them together.

“It must be nice to not only be an artist but to be your own Medici,” one of his disgruntled neighbours huffed to the New York Post, and after spending an afternoon with the man himself I can confirm that it does seem very nice indeed. While Koons strolls around in a quietly chic outfit of dark blue patterned shirt and blue trousers, young people in white coats skitter around doing what looks to me like most of the work: painting, sculpting, blowtorching.

“Maybe I’m not on each piece labouring over it,” he says, “but I’m overseeing each one tremendously.” Without help, he explains, he “would be able to make only one sculpture every few years. It’s about the gesture, that’s where the art is. It’s being able to work with people and to articulate ideas the same way you articulate your fingers.”

Koons, until very recently the world’s most expensive living artist, has the calm, unruffled air that, in New York, is generally only found in the heavily medicated. But in him, it seems more like the zen of a man who has all but the licence to print money. His works sell for multimillions. Art collector Peter Brant bought one of my favourite pieces by Koons – Puppy, a 40ft west highland terrier made out of flowers – and spends $75,000 a year just maintaining it. “Koons,” read one recent, and typical, critical assessment, “has made his name manufacturing toys for rich old boys.”

Of course, Koons hates this kind of chat. “The rest of the world talks so much about money,” he says, “and one of the reasons is I think they feel uncomfortable talking about art. So if they’re writing about art, and they don’t really want to talk about art, then they talk about money – and it’s like, ‘Whew! I didn’t have to talk about art!’” To which it’s tempting to respond: “Sure, Jeff, but it’s kinda hard to see the art when it has a $58m price tag hanging off its neck.”

This was Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) which in 2013 fetched what was then the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. But the day after our interview, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) was sold for $90m and Koons lost his title. Still, who cares about money? Koons’s claim to think only about higher things would, however, be a little more credible if he didn’t literally pink with excitement when we talk about the recent sale of the Edward Hopper painting Chop Suey: “Ninety-one million dollars! Wow!”

We’re meeting because Koons is preparing for his first big show in the UK since his 2009 exhibition at the Serpentine in London. I loved that show, with its re-creations of giant inflatable toys made from stainless steel and ludicrous Popeye paintings. (“Art for people with short attention spans,”Adrian Searle wrote in the Guardian. Hi!) But was it fun? No question – and it’s even more fun seeing those pieces and many more closeup in his studio.

His famous inflatable pieces are so realistic that when I reach out to squeeze what looks like a blowup plastic seal and find myself touching cold hard steel instead, the sensory confusion makes me burst out laughing. Scattered through the maze-like rooms in the studio are re-creations of his giant “porcelain” figures, also made from stainless steel. One, an especially kitschy image of two deer rubbing their noses together, looks like the kind of thing a little girl would pick out for herself in an airport giftshop in the 1980s, because that’s exactly what it is. “I had that figurine when I was a child!” I say in astonishment.

Koons nods, as if he expected as much. “That’s what I’m going for, that sense of familiarity, and you are open to it. The reason I work with readymades” – meaning already existing objects – “is to remove judgment and hierarchy. Every object is a metaphor for yourself.” In what way? “I try to make work to make you think everything is perfect in itself. It’s all a metaphor.”

What this response may lack in explanation, it more than makes up for in brilliant deflection – and if there’s one thing Koons is genuinely great at, it’s deflecting criticism. In early 2018, he announced that he was giving one of his sculptures – Bouquet of Tulips, which depicts a giant hand grasping some 38ft-high balloon flowers – to Paris as “a symbol of remembrance, optimism and healing” after the terrorist attacks in 2015. Alas, the city proved less than enthusiastic and high-profile Parisians, including film-maker Olivier Assayas, wrote a spectacularly vicious open letter criticising the “inappropriateness” of the gift.

“While he may have been brilliant and inventive in the 1980s,” they wrote, “Koons has since become the emblem of an industrial, spectacular and speculative art … Koons’s studio and dealers are hyper-luxury multinationals, and offering them such prominent visibility and recognition amounts to publicity or product placement.” This controversy roared on until October when a compromise was reached: the work will be installed in front of the Petit Palais, instead of the originally planned and much more prominent position by the Palais de Tokyo.

Surely this saga must have irked Koons? He makes a small smile that seems less like an expression of amusement and more like the donning of armour. “I remember back in 1985, I made a show called Equilibrium. A review came out and it looked at it in not such a positive light. I was really surprised because my intentions were so good. I think I learned early on that people just take positions without knowing everything, and these things can gain a momentum. I always believe, if people really open themselves up and just look at my work, they’ll realise the reason behind it and what my motivations are.”

In other words, if you don’t like Koons’s work, the problem is you, not him. The new show will be at the Ashmolean in Oxford, and it’s all thanks to some Oxford students who voted him their favourite contemporary artist. Koons came to give a talk, one thing led to another, and now he’s on display at the world’s oldest university museum. Like Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami, it is often said that Koons’s art is best experienced in person – to get a sense of its genuine spectacle, although I’m not sure I’d recommend asking Koons about this.

“I hope people who view the exhibition feel a sense of wow, but realise that wow is about their own being, and what gives them that wow is their own potential in the areas they’re most interested in, not in the areas I’m interested in.” Despite Koons’s emphasis on accessibility in his work –what he calls “removal of hierarchy” – it often feels like you need either a PhD or a lobotomy to understand his explanations.

Koons was born and raised in Pennsylvania, the son of a furniture dealer and interior designer. This was such a happy time that he bought the 650-acre farm owned by his grandfather, and he and his family go there every weekend. “My childhood was wonderful,” he says and that’s that. Despite his claims of openness, Koons is strikingly opaque about subjects he considers irrelevant to his art. In the 2014 book Jeff Koons: Conversations with Norman Rosenthal, the artist is asked if he likes movies. “I think the form of narrative that I’m involved with in my own art I find more interesting,” he replies.

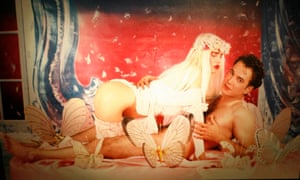

After studying art and working briefly as a commodities broker to make money, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s. “Let’s see, I did the Pre-New, the New, Equilibrium, Banality,” he says, ticking off his art series. “Then what came after that? Oh yes, Made in Heaven.” This began when Koons saw a photo of Staller, a porn star and Italian politician, in a magazine and set out to meet her. “I enjoyed very much that she was standing there without any pants on,” he later recalled.

He photographed them having sex and gave the works names such as Jeff Eating Ilona and said he was taking away sexual shame. Alas, he couldn’t take away sexual prurience so, while people queued round the block to see it, the art world cringed in embarrassment. When Staller moved to Italy with their son, Ludwig, leading to a long custody battle, Koons destroyed many of the works. Did he, despite his intention with this series, feel ashamed of the photos?

“Not at all! I’m still very, very proud of those works, but I was in a custody situation for my son and my ex-wife, Ilona, was saying that what I made was pornographic. So I decided that the works I could control I’d destroy, to help my chances of gaining custody.”

I met Trump a bunch of times and our children went to the same school – but I never knew him

A lot of people destroy photos of themselves with their ex. Is it not weird to look at pictures of you having actual sex with someone you split from so acrimoniously? “No, I look at it as art,” he says. Does Ludwig look at it that way? “I think my son understands what my motivations are,” he says, the shutters coming down.

In an article written in 2008, the New Yorker’s art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, said Koons told him: “I can’t vote for Hillary Clinton. She didn’t help Ludwig.” This was a reference to his desperate attempts to get his child back from Italy. When I ask Koons about this, he recoils. “I can’t speak to what I said at a certain time. But I was involved with the [2016] Hillary campaignand I supported Hillary.”

Did he ever meet Donald Trump, I ask, given they were in similarly monied circles in New York in the 80s? “I met Trump superficially a bunch of times and our children went to the same school. But I never knew him.” Shutters down.

Koons met his wife, Justine, when she worked in his studio. Surely it must be hard for them to keep their equilibrium with their six kids running around, even if they do live in a house the size of a multiplex? “Oh no, I love the freedom!” he says, with the smile of a man who has a serious amount of childcare.

Our time is up and as I get up to leave, he suddenly leans over and speaks urgently. “Can I ask you something? I’d prefer it if you don’t go into the political stuff,” he says.

And it’s at this point that I finally lose faith with Koons. I can enjoy an artist who works with banal ceramics, plastic pool toys, or even quasi porn. But one who prioritises his carefully cultivated blank image over engaging with the reality around him so as to maintain his elite everyman appeal? What’s the point of art anyway? Sorry, Jeff, I don’t buy it. Mind you, I couldn’t afford it anyway.

The Guardian

Leave a comment