By pushing through a soft Brexit, Labour could safeguard the economy and eject the Conservatives for a generation

Consider this scenario. The Brexit national crisis is resolved on terms that protect the economy and hard-won workers’ rights. The national conversation moves on to the NHS (remember that?), child poverty and housing. Another referendum, more poisonous and bitter than the last, and one that could easily be won by leave all over again, – polling currently shows more people would prefer to leave without a dealthan to stay in the EU outside of London and Scotland – is avoided. A transformative government comes to power which rips up a four-decade-old market fundamentalist experiment that has been an endless generator of insecurity and social turmoil. The Conservative party – which, for entirely partisan ends, has brought chaos and humiliation to Britain – is torn asunder, ejected from office for a generation.

This could be the prize if Labour agreed a deal with the Tories that forced Theresa May to reject her party’s red lines. There are the obvious pitfalls to be navigated: May using the talks to run down the clock, or to displace responsibility for a national calamity of the Conservatives’ own making to Labour, or to provide a pretext for a long extension that torments the Brexiteers. Every promise would have to be written in legislation and passed by the House of Commons, or be simply tossed on a bonfire by May’s hard-right successor. Labour agreeing to any deal with May will cause a paroxysm of fury from those remainers who – understandably anguished by this wretched mess – will be satisfied by no less than another referendum.

But if Brexit means a customs union, close alignment to the single market and legally binding protections on workers’ and consumers’ rights and environmental standards, then it is no longer a “Tory Brexit”, a fissure with the EU based on chlorinated chicken, polluted oceans and a race to the bottom. Such an arrangement seems unlikely to produce an economic shock – on the contrary, investment decisions delayed by uncertainty might produce a short-term economic boon. Brexit would have no impact on most people’s lives. Most would probably be relieved to move on from it.

This will probably not happen. That is not because the negotiations are simply a ruse by May, as was my own instinctive reaction. This would be to read Machiavellian intent in those without the strategic competence for it. Ministers are genuinely desperate. There is no dastardly plan, no ingenious scheme: just the terror of a general election, and a realisation that no deal will break both the country and the Tories. But while there are those, such as May’s de facto deputy, David Lidington, and her chief of staff, Gavin Barwell, who genuinely want a deal, there are others, such as Robbie Gibb, May’s director of communications, who apparently do not.

May’s shift in position has not come willingly. While David Cameron was a PR man who aspired to become prime minister because he thought he’d “be good at it”, May – a former councillor who spent many a rainy evening stuffing leaflets through letterboxes – has an overwhelming emotional attachment to the Tory party. She will not want to be remembered for breaking it, as striking a deal with Labour would do.

But that does not mean that a resolution of the Brexit crisis on terms that would break the Tories as a political force is not within grasp. This might read as crude partisan politicking at a time of national turmoil. Yet wishing to shatter the Tories is to put country before party. Britain’s worst postwar crisis is the product of two things: Tory economic policies, from deindustrialisation in the 1980s to austerity in the 2010s, that have bred mass disillusionment and discontent; and self-defeating attempts to gain short-term political advantage by Cameron and May.

And the Tories’ infection with rightwing populism has left them weakened and divided. It has detached them from their traditional core support from big business (“fuck business”, as Boris Johnson eloquently put it). Protecting the interests of this class from a Labour party committed to a radical redistribution of wealth and power would, in normal times, promote a sense of unity. A Corbyn-led government creates a genuine sense of terror for most Tory MPs. Ordinarily, the onward march of the red menace would underscore the need for iron discipline, but their internal divisions are too bitter and too great.

If, as is likely, the talks break down, the Tories must be held responsible. It is, as now ex-Tory MP Nick Boles put it, the Conservatives who are the party “least willing to compromise”. We must return to the indicative votes process. And if a referendum becomes the only means to prevent no deal, so be it. But putting aside what a fractious, unpleasant experience it would be, a majority of MPs continue to reject it.

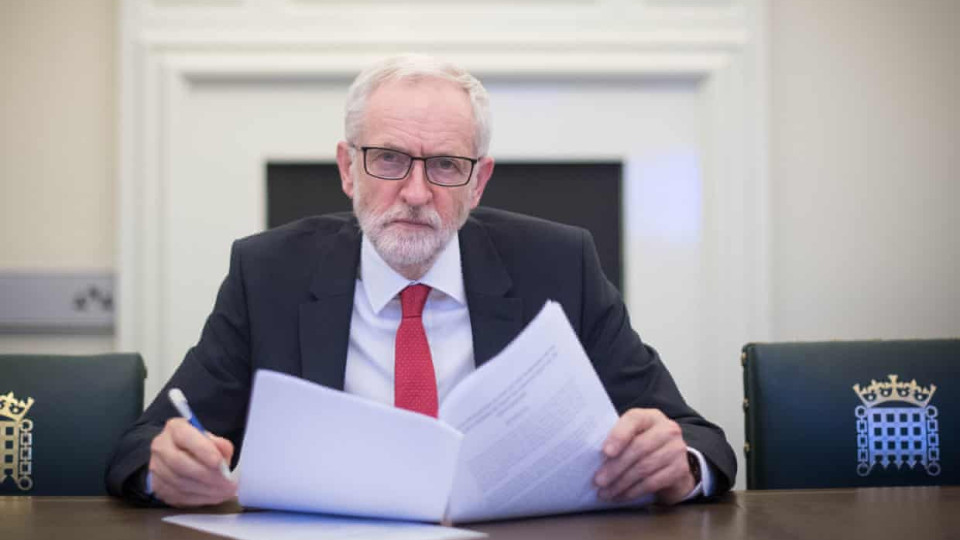

I believe there is, however, a theoretical majority for a soft Brexit in parliament, and so Labour must push for something along the lines of Norway plus, as it whipped its MPs to do last week. That places strain on Labour, because it would mean the continuation of freedom of movement, albeit with an emergency break. Labour’s failure to make a consistent, passionate pro-migrant case has been truly depressing, not least because its leading lights – Corbyn, John McDonnell and Diane Abbott – fought for migrants and refugees when it was truly unpopular to do so, during both New Labour and Conservative governments. The case for freedom of movement must be better made.

The story of the last four years has focused on Labour’s inner convulsions and torment: and those will not go away. But a truly existential crisis grips the Tories. If Labour is smart and quick-witted, it could not only resolve the Brexit saga, but claim another prize within reach, one that has eluded every Labour leader in the party’s history – the breaking of the Tory party for a generation or more.

The Guardian

Leave a comment