After Columbine, Dave Cullen swore he would never write about a mass shooting again. But over the next 20 years, he realised that he and other journalists had a duty to destroy the deadly myths they had helped create

As I drove down Highway 6 toward the Rocky Mountains on 20 April 1999, hoping to find this high school I had never heard of in Columbine, where shots had been reported but no injuries, I had no conception of what I was about to witness. What was happening inside that high school was unimaginable. What it ignited was far worse.

Who could have known what we were in for? The police weren’t ready: they surrounded the school and waited for demands that never came. There was no active shooter protocol; the “lockdown drill” was still unconceived and inconceivable. Why would we drill kids to hide from gunmen? None of us had an inkling that the school shooter era had begun.

The school shooter era. Even 10 years after Columbine, I still couldn’t perceive what we were living through in that way. No one could. It had been going on far too long, but it was hard to predict its endurance or trajectory. While I despise the media scorekeeping – awarding the killers titles like prizefighters, giving them exactly what they crave – one stat is worth noting: what was then the most notorious mass murder in recent American history no longer ranks in the top 10. Four of the five deadliest attacks in the US have occurred since then, three of them in the past three years. In a five-day period near the end of last month, the US suffered four mass murders in four different states: Louisiana, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Florida. This is not going away, it’s getting worse.

Twenty years later, I am still on this story not just because of what happened, but also because of how the media responded. We got it wrong. Absurdly wrong. We were shocked and horrified and desperate for answers, serving a public hungry for a reason for the “madness,” so we found an answer. It was wrong.

Since 20 April 1999, I have studied most of the major mass shootings and some of the smaller ones. I have written about them individually and collectively. I have joined the Academy of Critical Incident Analysis (ACIA) team in studying several incidents, including on-site studies at Virginia Techafter the 2007 shooting and in Las Vegas in 2017, and an off-site analysis of Norway’s 2011 Workers’ Youth League attack in Utøya. A troubling trend emerged: many of the mass murderers emulated Columbine killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. The FBI released more than 1,500 pages of documents about the horror at Sandy Hook elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut in 2012, when Adam Lanza killed 20 first-grade students and six members of staff, as well as his own mother. It details just how obsessively Lanza was following Harris and Klebold. He amassed a hoard of Columbine information on his hard drive, frequented a chat room dedicated to the attack, and role-played the killers in an online game. If only this were an isolated incident.

I experienced two breakdowns of secondary traumatic stress seven years apart writing Columbine, so I studied the subsequent tragedies at a safe emotional distance and swore I would never plunge back into the scene of a crime. Last year, when a shooting erupted at Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school in Parkland, Florida, I broke that promise, because Parkland seemed different. The Parkland students immediately led an uprising against lax gun laws. Emma González hit back. David Hogg called out adult America for letting children die. The nation was galvanised, and five weeks later, their band of high school students led one of the largest protests in American history.

Any reasonable observer outside the US would have concluded long before the Parkland shooting that something had to be done. In fact, as the death count rose, media and public attention had waned. The public advocacy group The Trace has studied media coverage of these tragedies, and measured a significant decrease in coverage by 2018. Nearly two decades into this epidemic, the US had settled into a state of defeatism.

We had good reason. In the wake of Columbine, America was united in one idea – that something had to change in three obvious areas: police, schools and guns. The police surrounding Columbine High had failed to consider the possibility that the gunmen had no demands. They just wanted to kill people. After considerable analysis, police forces across America upended their response to these attacks with the active shooter protocol. They now neutralise most major attacks within minutes, saving countless lives. Schools responded too, with threat assessment teams, lockdown drills and advance coordination with law enforcement, who now have blueprints to their buildings and alarm codes. The changes were swift, and dramatic, but they were primarily aimed at reducing the death count once bullets were already in the air.

We were botching the story. I had no idea that I might bear some responsibility for the children dying two decades later

On prevention? On minimising the ability of perpetrators to arm themselves to the hilt, US politicians responded with ... nothing. Worse than nothing, they have regressed. Columbine brought great hope for gun control, but almost no meaningful legislation. Politicians of all stripes were afraid of the power of the National Rifle Association (NRA). In 2000, vice-president Al Gore stuck his neck out. He defied the conventional wisdom that gun control was politically toxic, ran on it and lost the electoral college, by a whisker, in two southern states he should have carried easily. Either one would have led to him defeating George W Bush. Guns were blamed, and the Democrats went from squeamish on gun control to terrified.

In the media, meanwhile, we carry at least some of the blame for this spiralling problem. What I failed to grasp that day I arrived in Columbine was how we were botching the story – and the staggering ramifications of mislaid good intentions. I had no idea that I might be playing a role, and bear some responsibility for the children still dying around us two decades later.

My first clue came that evening, on my drive home to Denver. I had filed a report by phone to Salon.com in San Francisco. I flipped on the radio for some respite and there was no music. It was all Columbine all the time on every station, and the story I was hearing sounded alarmingly different from the one I thought I’d just witnessed. The “what” was exactly what I’d reported – “up to 25 dead”, though that would be proved equally wrong – but the “why” all over the radio was unnerving. I’d spent nine hours with students, cops and distraught parents in Clement Park, the huge grassy area surrounding the school, and still had no clue at all why those boys had done this, other than insanity – which would also be proved wrong. Every other reporter in the field had apparently uncovered their motives: the killers had targeted two groups, jocks and black people, and were obviously racists striking back against ruthless bullying. I was distraught. How had I missed all that? It was the biggest story I’d ever been a part of, and I’d blown it.

The next morning, I did something worse. I changed my story. I’d gone home and turned on the TV to see the radio story validated everywhere. I’d awoken to the morning papers and the TV news correcting the death count from 25 to 15, but trumpeting the primary narrative, still with us today, of two bullied, loner outcasts from the Trench Coat Mafia exacting revenge. It’s a powerful story, but entirely fictional. Every element of that narrative would turn out to be false. But that morning, the driving emotion for me was humility. Obviously, I was the one in the wrong.

It had all happened so quickly. Years later, I expected to trace the origin of the myth over the first week or two, analysing all the major newspapers’ coverage. But the genesis had to be measured in hours, not days, and the CNN transcript from 20 April told most of the story. It’s a remarkable document, because the networks cut between four local stations’ feeds, providing a cross-section of virtually all the live on‑site TV coverage. Most of the major myths still haunting us solidified in those first few hours. Over the course of that afternoon, reporters went from asking if the killers targeted jocks and black people, to asking kids to confirm reports of the targeting, to beginning to state it as a fact. There was a similar progression with the killers being bullied, loners, outcasts and goths.

The attack began outside, where every witness reported Harris firing indiscriminately. And two days later, two huge propane bombs were discovered in the cafeteria. It was clear that the killers had intended to blow up a wing of the school, killing close to 600 students instantly. Could that really be called targeted?

I have taken to calling them spectacle murders, because they are essentially performances – and without the media, they have no stage

The 23 April edition of the New York Times is chilling. The front page led with two Columbine stories, side by side. The story on the left explored the motives, unequivocally stating: “The killers, who targeting athletes …” The story on the right revealed the bomb discovery – disproving the targeting theory reported as fact beside it. Worse, the stories ran under a single banner announcing that the killers intended to “Destroy the school”. No one called them out on the absurdity – because nearly all of us were locked in the same cognitive dissonance, reporting it the same absurd way.

The jock theory hinged entirely on four words one of the killers shouted in the library: “All jocks stand up.” But they had shouted all sorts of slurs about every conceivable group during the slaughter. Why did we turn the jock phrase into the primary motive, and the explanation for the entire attack?

Because it made a great story. Not just to journalists, to the survivors too. The nation was desperate for an explanation, and bullying jocks made plausible targets. It didn’t just fit, it explained everything. So easy to imagine these outcast boys, ruthlessly tormented until they reached breaking point and struck back. So what if none of the evidence fitted?

The problem didn’t start with Columbine. Journalists began the afternoon with leading questions, and Columbine students acquiesced so easily, because smaller-scale school shootings had already been afflicting us, and there was a widespread “understanding” of the shooter profile: bullied loner outcasts. Both the FBI and secret service would later debunk those profiles, but there was little reliable data at the time. Past misconceptions were quickly projected on to the Columbine killers: imaginary heroes of the downtrodden concocted largely over the course of one afternoon.

In fact, the two were uninterested in their particular victims, just the body count. Mark Juergensmeyer, one of the great thinkers on terrorism, captured the essence of that phenomenon in one phrase: performance violence. A defining characteristic of terrorism is some sort of political agenda. But the Columbine killers realised they could employ those same tactics for their own petty self-aggrandisement. A whole generation of murderers have followed in their wake.

It took several months, but eventually all the major media concluded that we had the motive story hopelessly wrong. Within a year, most big print outlets had published some sort of correction. The problem was that hundreds of millions of people had gobbled up the early coverage – CNN logged its highest ratings in its history to that point, the New York Times page one featured Columbine for nine consecutive days – and hardly anyone noticed the corrections. They certainly didn’t dislodge readers’ entire conception of a seminal moment in modern American history. Myths are for ever.

I spent a decade after Columbine battling those myths, sorting the truth and eventually publishing a book, Columbine, around the 10th anniversary. Reporters still ask me what they should learn from the Columbine debacle, and I say get it right the first time, because we can never untell the myths we spin.

It was only in the second decade of the school shooter era that we discovered just how pernicious those Columbine myths would prove. An exhaustive secret service study found that most of the school shooters during that period were distraught and deeply depressed, with suicidal thoughts or intentions. Most felt a sense of loss or failure, and seemed to be crying out in desperation for a sense of power and a voice. They were rarely targeting the individuals they killed; the victims were collateral damage in the service of an impressive body count. I have taken to calling them spectacle murders, because they are essentially performances – and without the media, they have no stage. No voice. We play right into their hands.

The No Notoriety movement began to gain a foothold about a decade after Columbine, but didn’t really gain momentum until 2015. The manifesto at nonotoriety.com is quite modest and sensible, calling on journalists not to stop naming or showing killers entirely, but to “minimise harm”. It asks them to “limit the name to once per piece as a reference point” and downplay photos, for example, putting them below the fold in newspapers. Yet even though Anderson Cooper began refusing to name mass killers on his highly rated CNN show AC360, demonstrating how easy it was, very few shows followed. In 2015, People magazine became the first major publication to adopt a No Notoriety policy. In November 2018, BuzzFeed announced a new harm-reduction policy directing reporters and editors to end the gratuitous use of the names or images of mass shooters.

For many outlets, the problem remained that the killers tended to be more interesting than their victims – not just to journalists, but to readers and viewers. As the recent controversy around the forthcoming Ted Bundy film illustrates, humans will always be fascinated by criminal minds. It’s why cop shows dominate TV and crime fiction sells. We in the media can diminish the killers’ profiles, but as long as the audience craves stories about them, they will become famous.

In the case of school shootings, that conundrum seemed unsolvable – until the Parkland kids flipped the script. David Hogg became the first mass shooting victim to become more famous than his attacker. It took him less than 24 hours. Two days later, Emma González went viral with her “We call BS” speech and was a household name across the US and much of Europe. In her first week on Twitter, she surpassed a million followers. Their attacker is a nobody.

When writing my book about Parkland, I chose to erase the killer’s name. It was an easy choice. He is insignificant. We need to study these killers as a class, but the FBI has done that. It wasn’t a tough decision, though. The Parkland kids made it easy. I didn’t go to Parkland to cover the gunman, I went because I was fascinated by the students. America was fascinated. The world was fascinated. In November, Archbishop Desmond Tutu bestowed on them the International Children’s Peace prize, calling their campaign “reminiscent of other great peace movements in history”.

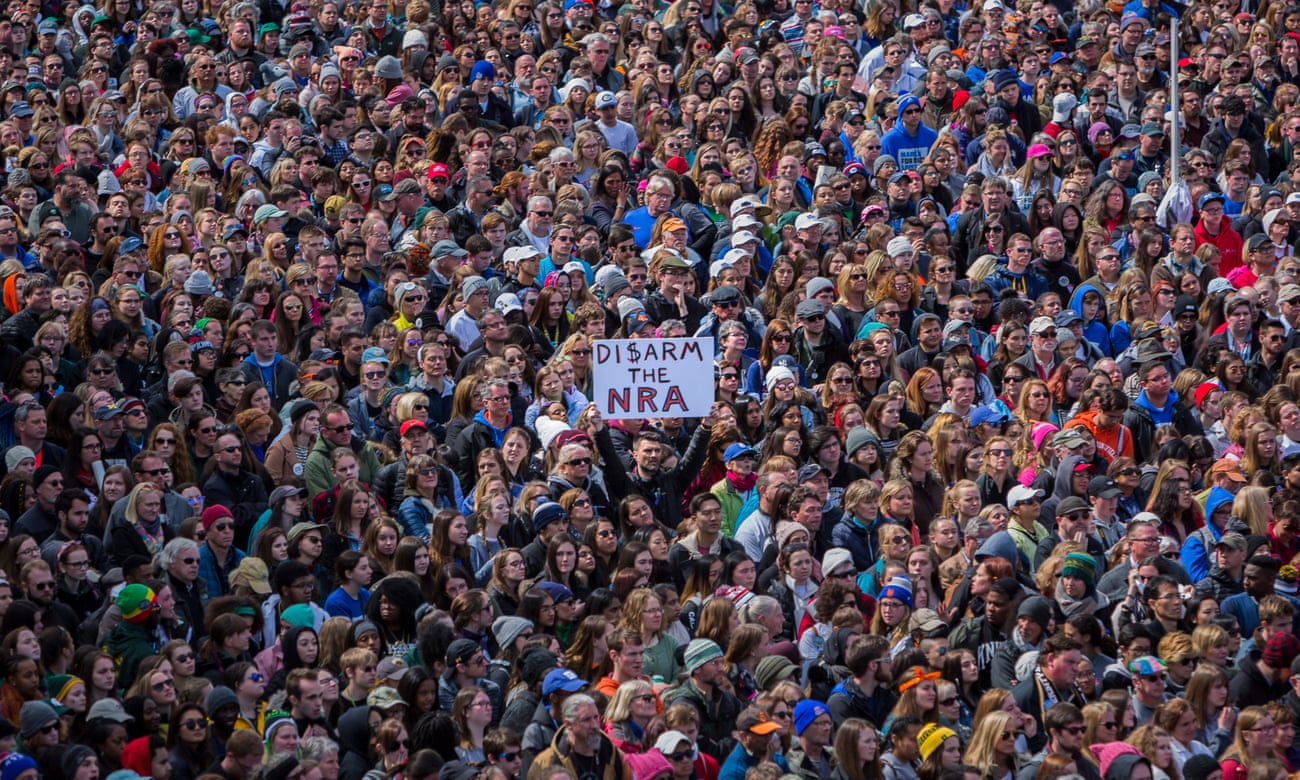

The Parkland students decided in the first few days that they needed to speak with one voice, and focus on gun safety. March for Our Lives followed on 24 March 2018. Estimates state that between 1.4 and 2.1 million people marched in the US that day, making it the third or fourth largest one-day protest in American history, equivalent to the largest protest of the Vietnam war era, led by college students, who had been rallying for the better part of a decade. The Parkland uprising was organised by high school students in five weeks.

When Parkland was attacked last Valentine’s Day, supporting gun safety was considered politically toxic. Suddenly, for the first time in a generation, it is starting to grow politically toxic to oppose it. The NRA is not rolling over and the battle will rage for years, but the Parkland kids have achieved stunning success in the first year. State legislatures reversed the NRA momentum, passing 67 laws tightening access to guns. But the big prize was the November midterms. Democrats finally stopped cowering on gun laws, ran on reforming then, and retook the House of Representatives. Even Republicans in some key swing districts ran on gun safety. They didn’t all win, but the movement exceeded the wildest expectations last February of what they might accomplish.

The Parkland kids have also helped to solve another problem: robbing spectacle murderers of the spotlight they crave. I was pleased to discover that, while doing media interviews for my book, hardly any journalists could recall the Parkland shooter’s name – even those who had covered the story. Yet millions of American schoolchildren can name a dozen of the March for Our Lives kids, and follow them daily on social media.

These survivors have truly eclipsed their killer. The solution was very simple: they did something more powerful.

The Guardian

Leave a comment