Learning from this mess, we must cut the ties that bind the state and key professions to a tiny number of schools

Among the myriad absurdities of Brexit, one has repeatedly taken the whole thing into the realms of the surreal: the gifting of the whip hand to the Tory faction known as the European Research Group. At the start of yet another watershed week, it is still this 90-strong band of ideologues that holds the keys to both Theresa May’s political future and the fate of her deal. Faced with a third meaningful vote, will they accept that their only remaining options are the prime minister’s version, or such a long delay that their dream will start to fade? Once more the spotlight will shine on their de facto leader, Jacob Rees-Mogg. This one-man embodiment of the mess into which we have all been dragged is reportedly coming round to supporting the withdrawal agreement, and “seeking a ladder to climb down”.

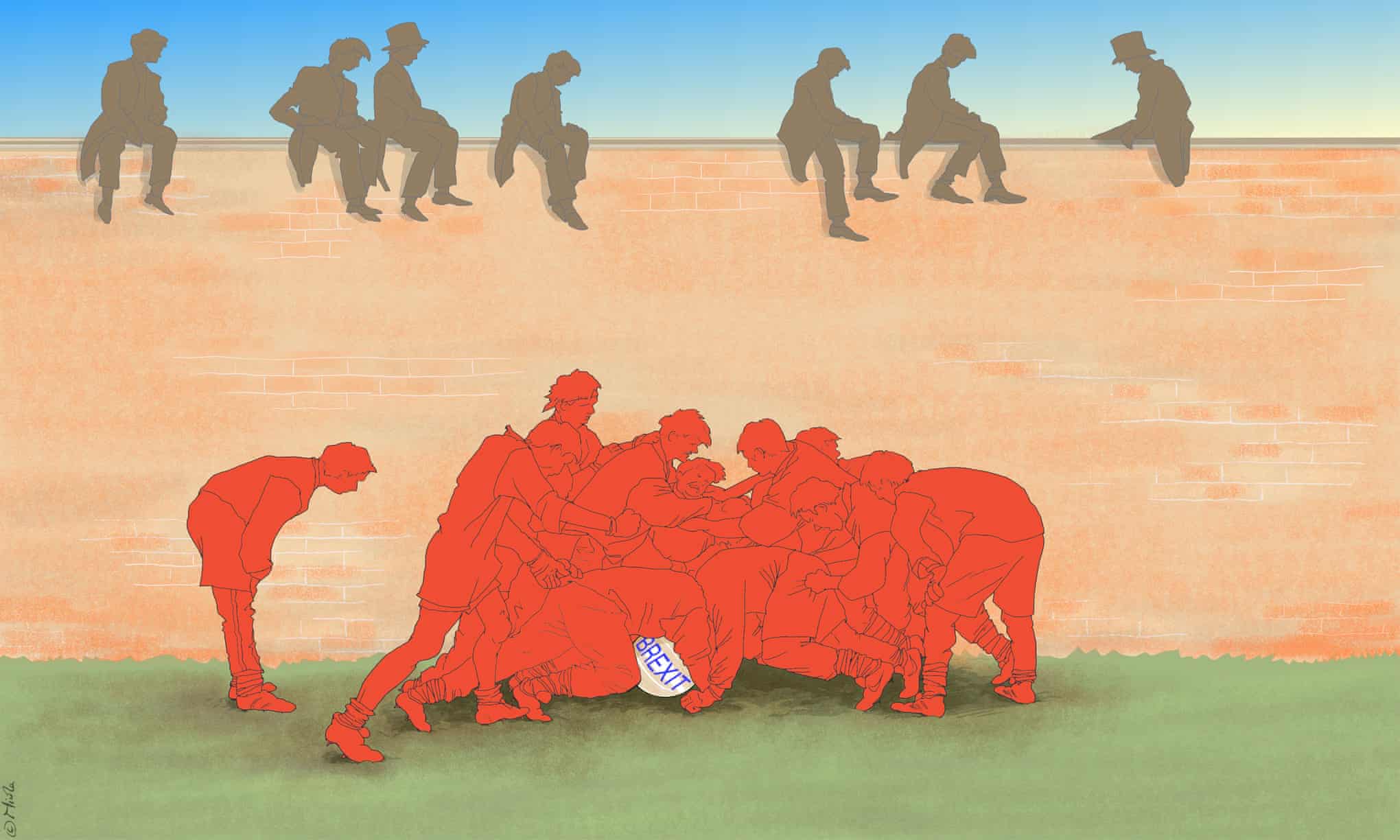

Where did he come from, this human museum piece? His late father William’s editorship of the Times, conducted according to instincts described by one obituarist as both “economically dry” and “socially conservative”, is one part of the story. Another goes even further back, to the roots of the Rees-Mogg family wealth, in the ownership of coalmines in Somerset. This is the same county where Rees-Mogg now represents such fading former pit towns as Radstock and Midsomer Norton, places replete with the ghosts of a lost industrial past and the consequences of the austerity that he has enthusiastically endorsed. At university, Rees-Mogg was a nightly presence in the debating hall of the Oxford Union. His apparent skill in matters of high finance – which, according to a recent edition of Channel 4’s Dispatches, has earned him an estimated £7m since the referendum, assisted by the fall in the value of the pound – goes back to childhood dealing of stocks and shares, and time spent in Hong Kong and the City. The most telling element of his background, however, is surely the school that saw to the key five years of his education – Eton College. This institution sits at the heart of the Brexit mess and the dismal political failings that led to it. What comes to mind at the mention of Eton? Tailcoats? The eternally mysterious wall game? Or the angry lament contained in the Jam’s Eton Rifles, with its Larkin-esque opening line: “Sup up your beer, and collect your fags / There’s a row going on, down near Slough”, that lyrical portrait of a working class serially defeated by privilege (“All that rugby puts hairs on your chest / What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?”). Eton chiefly symbolises the unbroken English link between private education and power. To quote one old boy, who did his time in the 1980s: “Kids arrived there with this extraordinary sense that they knew they were going to run the country.”

And so it continues. Thanks to such things as tiny class sizes, entry-level networking, the cultivation of breezy confidence, and well-trodden pathsstraight to Oxford and Cambridge, Etonians and the alumni of other “top” private schools are still at the core of British rightwing politics. Their fingerprints are all over Brexit. David Cameron was deluded enough to call the referendum in the first place, blithely ignoring the possibility that the cruelties of his austerity programme would inform the public’s response. The list of privately educated figures centrally involved in the campaigns to leave the EU runs from Daniel Hannan and Douglas Carswell to Nigel Farage and the Vote Leave campaign director, Dominic Cummings.

Thanks to his brazen embrace of a cause he thought would smooth his passage to the Tory leadership, Cameron’s Eton contemporary Boris Johnson led the push to exit the EU, positioning the campaign far enough from the Ukip fringe to ensure its victory, and is now the bookies’ favourite to be the next Tory leader. In the nightmarish eventuality that he made it to No 10, he would be the 20th Etonian to do so. Rees-Mogg, meanwhile, has spent the past three years stoking the fury of what remains of the Tory membership, thus doing his bit to ensure that May’s successor will have to be a hard Brexiteer. Even if most ERG MPs finally fall in behind her deal, he and his allies will continue their mischief and sabotage, as the UK becomes immersed in negotiations about our future relationship with the EU.

It is no accident that, as the scale of the Brexit disaster has grown, two high-profile books – David Kynaston and Francis Green’s Engines of Privilege, and Robert Verkaik’s Posh Boys – have been published tracing the history of so-called public schools and their domination of our power structures. However Brexit is eventually settled, we will sooner or later have to deal with this fundamental dimension of how the mess happened. The past three years of British history have proved that privilege often breeds a dangerous mixture of ineptitude and arrogance, as well as incubating the kind of unhinged ideas that could appeal only to people removed from ordinary life, who tend to see the world in terms of crass abstractions. This, incidentally, is something proved by any number of posh revolutionaries, and is evident on the modern political left as well as the right.

In response, the rest of us ought to push the idea that people with power and influence ought to have an innate understanding of the very complex ways that power and policy affect ordinary experience, and the kind of scepticism about grand schemes that is rooted in the real world.

Brexit should focus minds on how we begin to cut the ties that bind the state, politics and key professions – including journalism – to a tiny number of schools. There is no need to abolish private education. The simplest solution might prompt outrage, but would be no more drastic than Brexit itself. As well as an end to private schools’ charitable status, it should be demanded, via legislation, that over the next 10 years or so Russell Group universities allocate their places in line with the balance between private and state schools in the population at large, so that 93% of their students are eventually state-educated. I am not sure whether this would deprive politics of future Camerons, Farages, Johnsons and Rees-Moggs; it is pretty clear that some of the most out-there Tory ideas run deep among Conservative MPs who went to comprehensives. But it does strike me as the reasonable basis for a deep cultural change that is at least 50 years overdue.

Just to make one other thing clear: obviously, it is more than possible to go to Eton, or Harrow, or any number of other fee-paying schools, and emerge as humble, sensitive and self-aware as anyone else. I have also met people profoundly damaged by the experience of private school, even when everything has gone to plan. They were usually all too aware of what was successfully inculcated in many of their peers. A letter written to the Guardian in 2011 made the basic point: “As an escapee from one such institution, my experience is that the ethos instilled largely consists of overweening arrogance, a total inability to admit errors, and a feeling of innate superiority to the rest of the population, leading to such joyous public-school-led adventures as the Iraq war and the banking crisis.” Brexit is the latest item on the same list. If any good is to come of Britain’s current breakdown, it ought to be the last.

The Guardian

Leave a comment