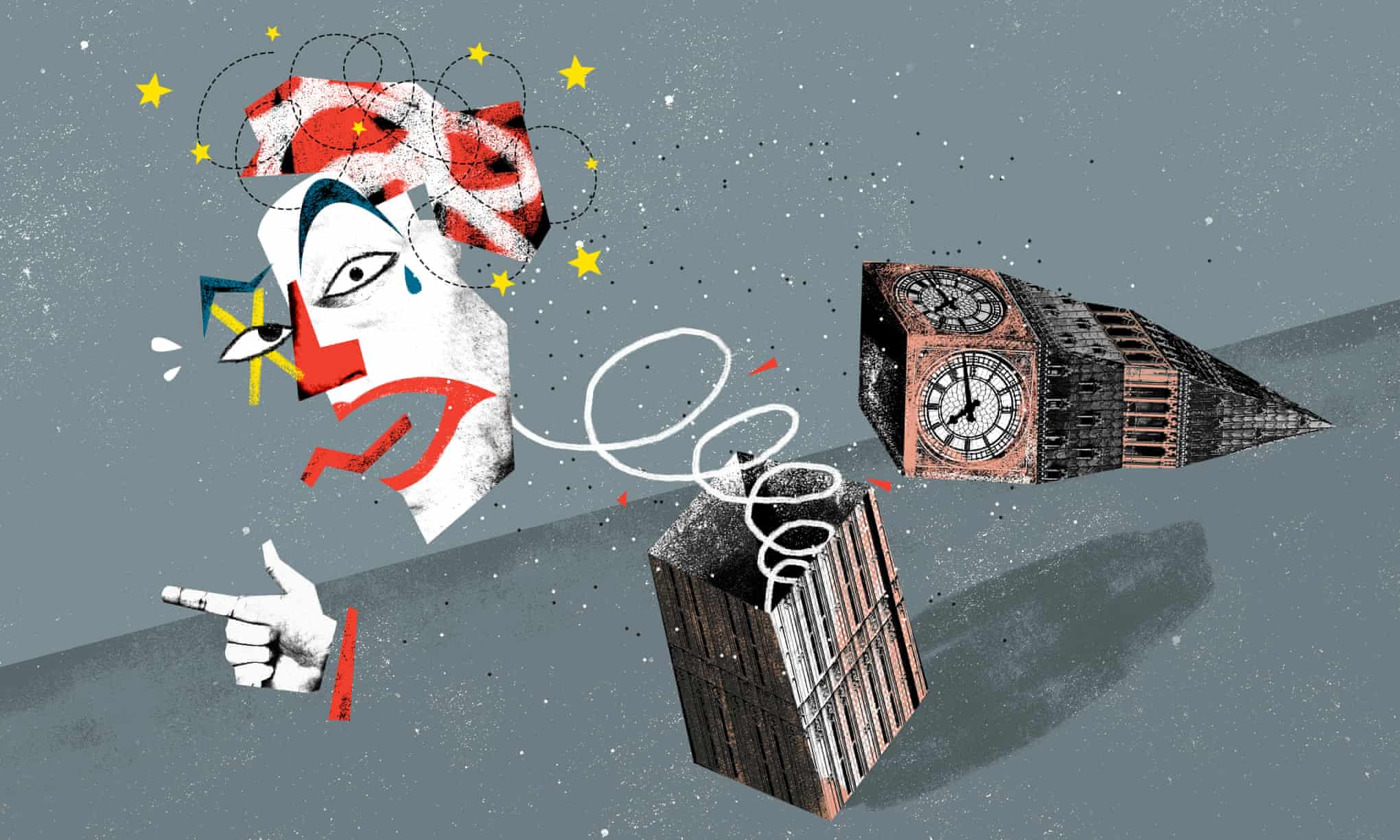

We are an international laughing stock at the moment. But something like this has been coming for decades

The French EU minister, Nathalie Loiseau, has called her new cat Brexit. “He wakes me up every morning meowing to death because he wants to go out,” she says. “And then when I open the door he stays put, undecided, and then glares at me when I put him out.” The Dutch prime minister has compared Theresa May to the knight in Monty Python who has all his limbs lopped off and insists “It’s just a flesh wound” and calls it a draw. “She’s incredible,” says Mark Rutte. “She goes on and on. At the same time, I do not blame her but British politics.” Italian friends tell me Brexit now comes on at the end of the news, in that wacky slot just before the sport and weather.

Everybody is laughing at us. Why wouldn’t they? We look ridiculous. If we weren’t so busy feeling betrayed, bored, enraged or bewildered, we’d be laughing at ourselves. Brexit, according to many of its advocates, would give us the chance to stand tall and independent again: to fulfil the potential, as May put it two years ago, to become “a great, global trading nation that is respected around the world and strong, confident and united at home”. Instead we look like a cross between a beggar and basket case. Yesterday, May pleaded for more time, and the EU said: only if you can get parliament to agree to your deal. May, displaying all the skills of brinkmanship and diplomacy that has got us to this point, then went and insulted parliamentarians, making them more hostile and fearful for themselves than ever.

Two crises have been revealed by these events. The first relates exclusively to Brexit. With eight days to go, we have a deal few want and a timetable that can’t be changed without agreeing to it. The EU may soften its terms; MPs may change their minds. We have just over a week to either find a unicorn or convince ourselves that the donkey we got for Christmas was a unicorn all along. This awful game of chicken was May’s plan all along – waste time until the “choice” was between her deal and no deal. This would be a breathtaking gamble in the hands of the most gifted or charismatic politician. She has proven herself to be neither of those things.

The second crisis is more enduring. It can be seen in the complete breakdown in Tory party discipline, with cabinet ministers voting against the government and backbenchers in uproar. It is evident in the disintegration of party loyalty. Conservative MP Nick Boles quit his local association while remaining a party member, claiming the people who selected him have “values and views … at odds with [his] own”. Eight Labour MPs left the party to form the Independent Group. Both parliamentary parties stand terrified of their membership. Many Tory MPs are saying they will resign the whip if Boris is elected leader; it has taken three and half years, a failed coup and a successful election campaign for the parliamentary Labour party to come to terms with Jeremy Corbyn, and the threat of further mutinies still lurks. We have a hung parliament in which it is difficult to find a majority for anything, in which the Speaker had to invoke a four-century-old precedent to stop the prime minister bringing the same question to the house until she got a different answer. That breakthrough lasted all of one day.

This is a crisis in our polity – the norms of our political and electoral culture that has parties at its centre. It is now approaching full-scale collapse. Conventional wisdom has it that Brexit has precipitated this crisis. The crude question of remain or leave was always going to create divisions, embolden renegades and undermine moderates. Depending on your prejudice, once the country opted to leave by a narrow margin, it presented the political class either with the challenge of committing an irresponsible act responsibly or fulfilling the will of the people. Either way, our politics has proved inadequate to the task. Brexit has broken us.

But by ignoring what was going on in the country before June 2016, and trends beyond our shores, this gives too much credit to the Brexit vote. That didn’t create this dysfunction and dislocation, it all too powerfully illustrated it. Up until that point, the two most persistent trends in postwar electoral politics were the decline in turnout and waning support for the two major parties. Between 1945 and 1997, turnout never went below 70%; since 2001, it has never reached 70%. Meanwhile the two-party landscape that once dominated our first-past-the-post system has frayed. Fewer people want to vote and even fewer wanted to back the two main parties (these trends have reversed slightly since 2001 but are nowhere near where they were). In 1950, Winston Churchill won 38% of eligible voters and still lost. The year before the referendum, the Tories got a majority with just 24% of the eligible vote.

This is how we got to a place where all the mainstream parties, the unions and business representatives could back remain and the country could vote leave. It’s not Brexit that’s caused the crisis in our politics; it’s the crisis in our politics that’s made Brexit possible.

That crisis is by no means unique to Britain. Since the 2008 economic crash, most countries across the west have seen electoral fracture, the demise of mainstream parties, a rise in nativism and bigotry, a marked increase in public protest, and general political dysfunction. The gilets jaunes are still out every Saturday in Paris; the European parliament has concluded that Hungary poses a “systematic threat” to democracy and the rule of law, and the conservative bloc has expelled Hungary’s ruling party; Estonia’s ruling party is contemplating inviting the far right into government; Italian humanitarians are being threatened with jail for saving drowning refugeesand bringing them home when the government wouldn’t; antisemitism is on the rise across Europe with a 60% rise in the number of violent attacks in Germany; protesters in Serbia stormed national TV calling for media freedom. All of this before we mention the preening authoritarianism of Presidents Donald Trump of the US and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil.

The broad narrative arc in most places is similar, and in some cases even more pronounced, than the one that brought us Brexit. The key difference is that Brexit comes complete with a timetable, a deadline, and an entity – the EU – that has thus far escaped these trends because it is subject to the diplomatic pressure of governments rather than the popular pressure of voters.

It is difficult to imagine a scenario where Britain does not continue looking ridiculous for some time to come. We deserve to be laughed at. But those who laugh hardest should beware they do not choke on their own hubris. This virus that made this madness possible is highly contagious. We may, as yet, be the worst affected. But we will not be the last.

The Guardian

Leave a comment