The Rembrandt of the housing estates found lyricism in Tile Hill, capturing a changing Britain. Now he’s celebrating the books, records and T-shirts that triggered his artistic awakening

There’s a photograph of George Shaw, taken in 2002, that shows the Coventry artist gamely attempting to relive his youth. Facing the camera, he’s squeezing himself into the tiny Joy Division T-shirt he bought back when he was a skinny 14 year old. It looks more like a crop-top in the picture, barely reaching his belly button and pulling at his broad shoulders. “I remember my wife saying, ‘Stop it, you’re going to tear it!’” Shaw, who would have been in his mid-30s when the shot was taken, laughs at the memory.

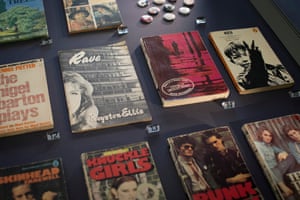

It’s a silly photograph, but also a moving one that explores – as most of Shaw’s work does – the passage of time, the roots of who we are and the melancholy of approaching middle age. The photo – and the T-shirt itself – are currently on display as part of a small exhibition at the Paul Mellon Centre in London revealing all his pop cultural influences: vinyl by the Fall and 2-Tone pin badges stand alongside pulpy skinhead novels and Ladybird books about trees.

“I’m always quite interested in the soil things grow from,” says Shaw, now 52, when we meet at the centre. “I thought showing people these influences might be more interesting than everyone thinking it all came from Constable or Turner. My entry level into Romanticism was [Factory Records designer] Peter Saville. It wasn’t the National Gallery.”

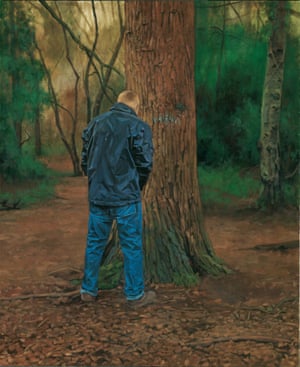

The exhibition is linked to a major retrospective of Shaw’s work at Bath’s Holburne museum. It is largely comprised of Shaw’s paintings of Tile Hill, the estate he grew up on that has obsessed him ever since he started painting. The drizzly visions of an empty, everyman England transcend their bleak settings, inviting viewers to project on to them their own childhood ennui. A rope dangling from a tree, a lock-up garage left open, a broken goalpost: each one suggests possible youthful adventures – or traumas.

Back in 2011, they gained him a Turner prize nomination. “There’s nothing like them in existence, either in writing or in painting,” says Mark Hallett, who helped curate the show. “Certainly not as rich or complex in terms of chronicling a particular kind of place – the British council estate – which has been so important in postwar Britain.”

Sorting through his childhood influences has been illuminating for Shaw: together they form a kind of self-portrait revealing new things about their subject. He’d always assumed his ideas came from Samuel Beckett or Proust, yet now he could see the path his artistic development took, starting as early as the Ladybird books, which were illustrated with the same lack of flamboyance he sees in his own work. There are several Ladybird books on display – including one on Great Artists – but it’s The Gingerbread Boy that seems to have struck a chord with the red-headed artist. “Because that was me,” he says. “Every fight in my life has been over the colour of my hair.”

Did he get beaten up a lot? “If I said yes, it would make me seem more interesting wouldn’t it?” He smiles. “I was certainly beaten up a lot more than I beat up. There were big lads hanging around, and that made the myths of fairytales seem all the more relevant.”

Shaw’s collection of pin badges attest to a well-cultivated outsider status – the Fall and Throbbing Gristle. “People at school would be listening to the Jam and they’d see a Joy Division badge and say, ‘Who the fuck are they? That’s just arty farty poofty wank!’”

There was one band, however, that did unite Shaw and his classmates. He says it felt tremendously exciting going into school the day after “from Coventry, the Specials!” had been uttered on Top of the Pops, and he still marvels at the access locals had to the group. “You could get on a bus and go stand outside their house,” he says. “It was like the Beatles in Help! – they’d come out and have a chat with you.”

The Specials inspired some of Shaw’s early art – he’d paint homeless people and kids he’d see in the streets of the ghost town. “I would have liked to have formed a band, but if you haven’t got any friends…” He trails off, making a comedy glum face.

There's a reason my stuff was ignored. It were shit

It’s hard not to make the connection between Shaw’s work and the Smiths record in his collection (Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now, featuring pools winner Viv Nicholson as the cover star). When he was younger, Shaw would visit galleries with his dad, marvelling at the artwork but feeling a sense of alienation from their grand settings. The paintings they constantly painted said nothing to him about his life – hence one of the motivations for the Tile Hill series, which contain references to all sorts of masters, from Rembrandt to Poussin, while placing them firmly in the present day.

“It felt liberating to find this language in paint that could articulate a kind of folkism,” he says. “And suddenly I wasn’t ashamed of saying I was an artist. Even now, I can go to the pub down the road, and if someone asks what I do I can tell them I’m a painter and show them my work. Whereas if I was making abstract stuff I’d be going…” He hangs his head in mock embarrassment, the stereotypical Midlander uncomfortable with any trace of pretension.

The Tile Hill estate is located on the edge of Coventry, where the city ends and woodland begins. These woods have long been a fascination for Shaw, and it’s no coincidence that some of the vinyl sleeves in the Paul Mellon collection – The Fall’s Live at the Witch Trials, Echo and the Bunnymen’s Crocodiles – feature trees. Shaw decided to explore these woods for his My Back to Nature series, painted while he was the National Gallery’s artist in residence.

Wandering around the gallery alone, he started to notice the sheer debauchery going on on the walls, and made the link to the goings-on in his own forests. Where Titian might paint a nymph writhing in sexual pleasure, Shaw saw the equivalent in the discarded pages of porn magazines that would be blown through the forest. There’s a wonderful video of Shaw browsing the National’s collection, unable to stifle his giggles as he points out various lewd Carry On-esque scenes embedded in the classics.

“It wasn’t what I wanted to do when I went to the National Gallery,” he says. “That was what I used to do as a kid. So I’d hoped that when I went to the National Gallery as a serious artist in residence, it might be an opportunity for me to grow up.”

He remembers his dad being similarly unable to keep a straight face during their visits there when he was a child. “He’d be saying, ‘Look at this great painting by Piero della Francesca – and the guy at the back in his Y-fronts.’ So there was always this loftiness mixed with a sort of earthiness, the sacred and the profane, which is a very English thing. I think that’s what makes some of the British art of the 90s interesting. It has an artiness and pretentiousness about it, but at the same time it’s taking the piss a bit.”

Shaw is the same age as the Young British Artists whose careers exploded in the 90s. Back then, his work involved more cutting-edge methods – film-making, performance art. When nobody came knocking to make him a superstar too, he felt he’d missed the boat. “Although there was a reason why my stuff was ignored,” he concedes. “It were shit.”

It must have come as a surprise, I say, that recognition arrived along after he’d turned his hand to the less fashionable world of paint. “Oh yeah, it’s still a surprise,” he says. “Even today it’s a surprise, I’m surprised that you’d want to talk to me. Why do you think I turned up? I don’t think I deserve any interest at all.”

When he was nominated for the Turner, he wrote about being worried that he would finally get found out. “Yeah,” he says, “Because there’s nothing remotely magical about any of it. About my take on anything or my ability or nothing. There are better painters, better collectors of music, better everything. So every time I do an interview I’m thinking, ‘You should really go and see this painter instead.’”

I often think I'm finished with Tile Hill. Then I'll visit my mum, pop out for a walk – and get inspired once more

Hallett, who’s nearby, rolls his eyes. He points out just how much American audiences loved the retrospective when it was in the US last year – not for its quaint Britishness as much as for its relatability, which survived the trip over the Atlantic. Even Shaw concedes that he’s often told a pond or a tree will remind someone of something and he’ll think: “You were brought up in Sweden. What the fuck are you talking about?”

But of course, the pond or the tree is not what people are really seeing. “It’s more the increasing distance between myself and the place I grew up,” he says. Shaw cites Rembrandt’s decade-spanning series of self-portraits as an influence, before returning to his pop roots: “I just wanted to make a painting that had all the feeling of the Beatles’ In My Life, or I’d Rather Not Go Back to the Old House by the Smiths.”

His Tile Hill paintings certainly succeed in this. To look at them is to see a life reflected back in all its fullness. Perhaps that’s why he keeps returning. “I often think I’m finished with them,” he says. “Then I’ll visit my mum who still lives there, pop out for a walk, and I get inspired once more. My wife will say, ‘Oh no, not again.’” He shakes his head, exasperated by his lack of free will.

“In a sense, I’m painting my own departure – to keep going, until the final painting is empty, and you’re no longer casting any shadow on it.” He muses on this for a while. “That’s when you paint the greatest painting of your life. But the fact is, you’ll never be around to paint it.”

• George Shaw: A Corner of a Foreign Field is at Holburn Museum, Bath, until 6 May. The complementary exhibition Secondhand Daylight is at Paul Mellon Centre, London, until 3 May.

Leave a comment