Some liken the damage wrought on Venezuela’s second city to a natural disaster. Others suspect Satanic intervention.

“El demonio,” says Betty Méndez, a local shopkeeper, by way of explanation for the wave of looting and unrest that convulsed Maracaibo earlier this month.

Most, however, describe the mayhem in psychiatric terms: a collective breakdown that shocked this lakeside city to its core and offered a terrifying glimpse of Venezuela’s possible future as it sinks deeper into economic, political and social decline.

“Horror, fear, despair,” said María Villalobos, a 35-year-old journalist, weeping as she relived three days of violence that many here call la locura – “the madness”.

“I thought it was the start of a civil war.”

Her husband, Luis González, nodded grimly in agreement as they recalled watching hundreds of looters – some wielding axes, sledgehammers, machetes or even pistols – move into nearby warehouses, shops and even a church to begin a frenzy of wrecking and theft. “It was as if they were possessed,” the 39-year-old driver remembered.

Maracaibo’s “madness” began on the night of 10 March – three days after a catastrophic blackout plunged almost the entire nation into darkness. But it had been long in the making thanks to years of economic and political neglect.

The 1.6m residents of Maracaibo – an oil capital once celebrated as Latin America’s answer to Houston – complained of shortages of water, electricity and fuel and a worsening public transport system even before Venezuela’s crisis began to accelerate in 2016, with the onset of hyper-inflation.

“There are communities here that go days, weeks or even months without water,” said Juan Pablo Guanipa, a local opposition politician. “It is a shattered city.”

Protests – like power cuts – are a daily fixture for maracuchos. Within 90 minutes of arriving last week the Guardian stumbled across a demonstration – residents of an inner-city neighborhood who had barricaded one of Maracaibo’s main arteries with tires, bricks and logs to protest against the lack of water.

“It’s as if we’re living through a constant war. Every day is a struggle,” complained one of the protesters, a 31-year-old mother of four called Yelenia Barrera.

When the lights went out on 7 March, that daily struggle became even tougher. The six-day blackout – which Nicolás Maduro blames on “terrorist saboteurs” but is widely believed to have been caused by a bush fire that crippled a key section of Venezuela’s grid – caused a domestic drama and an international scandal: one of the world’s great energy producers incapable of providing power to its people.

On Monday Venezuela suffered another massive electricity failure reportedly affecting at least 16 states, with officials again accusing Maduro’s political foes and their “imperial masters” in Washington.

When the first blackout struck the capital, Caracas, earlier this month, the wealthy scrambled for shelter in luxury hotels that still enjoyed light while the less fortunate were left to collect water from springs or toxic rivers.

In Barquisimeto, another severely affected city, some even bathed in the sewers as the blackout dragged on.

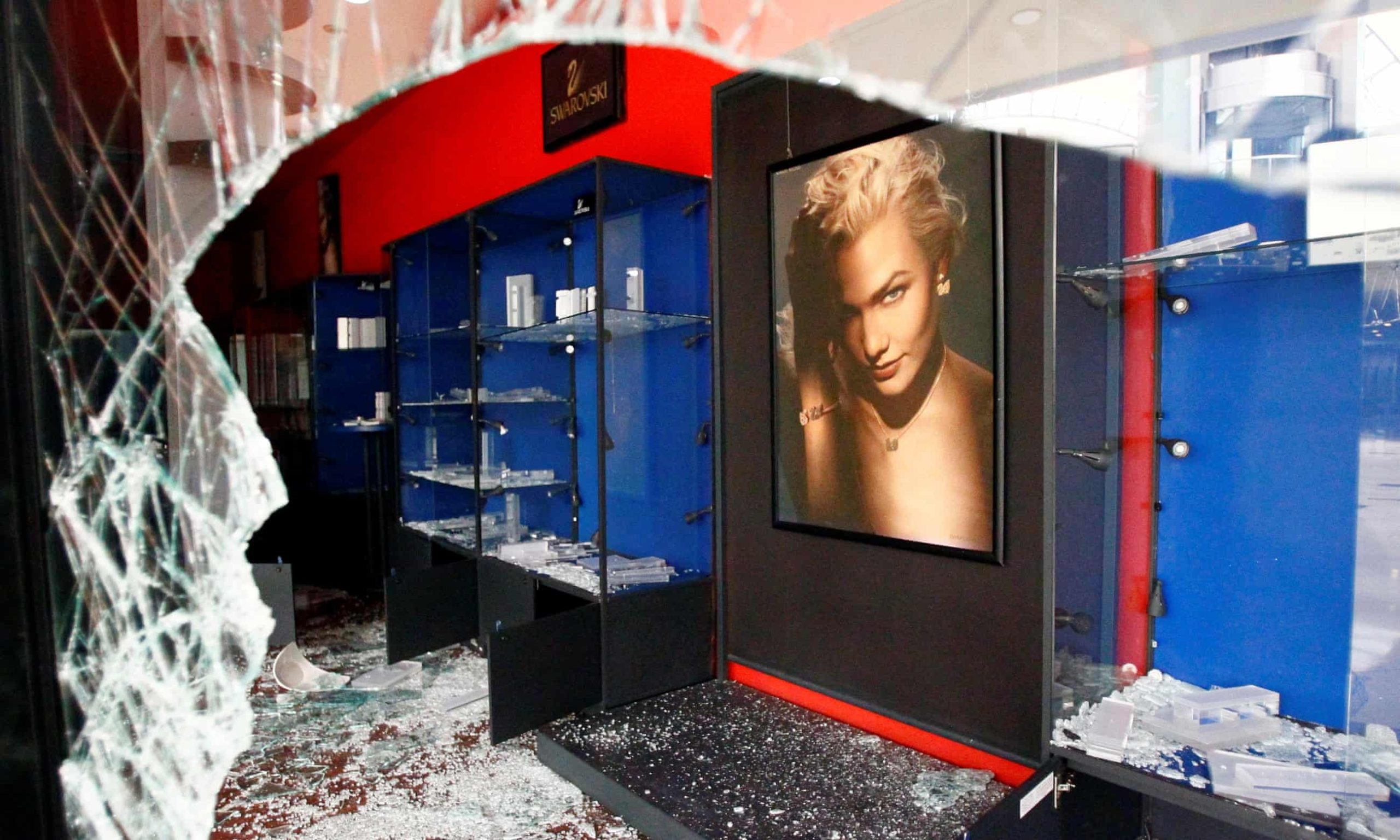

But the impact was most dramatic in Maracaibo, where a lack of electricity, information and police sparked disorder that security forces seemed unable or unwilling to control. Hundreds of businesses were ransacked or torched as residents stayed in their humid, light-less homes waiting for an explanation that took days to arrive.

“The pot was boiling – then it exploded,” recalled Juan Carlos Koch, the manager of a mall that saw 106 of its 270 shops raided.

Even worse hit was the Brisas del Norte (Northern Breeze) hotel, a five-storey guesthouse destroyed by a gang of about 100.

Not even an azulejo depicting the Virgin of Carmen at the hotel’s entrance was spared when the compound was stormed at around 9am on 12 March and 72 hours of looting and demolition began.

“A tsunami,” murmured its sales manager, Simaray Cardozo, as she loitered outside the wrecked reception, photocopies of guests’ passports and glass still strewn across the floor.

Inside, the destruction was absolute. Plaster ceilings had been ripped open to extract copper cables and pipes. Toilets, sinks and showers systematically stripped from each of its 120 bathrooms. Even the plug sockets had disappeared. Out back, a palm leaf parasol had been tossed into the half-empty swimming pool as a final insult to the owners.

As she toured the hotel’s pizzeria, manager Margelis Romero said she feared Venezuela’s economic decomposition was causing a moral one, pitting ordinary citizens against each other in a Darwinian scrap for survival. “I think it is social damage. They have damaged us so much, so, so much, that we have started to turn on one another,” she said. “Society is so disturbed.”

Romero wondered whether she too might one day find herself among the looters, if Venezuela’s crisis was not resolved: “How will I survive? Will I have to steal too? I’ve also got kids to feed. What happens when I can’t? How will I react?”

Leonardo Pinzón, another employee, was less understanding. “They are terrorists – not looters, terrorists,” he said.

Local politicians and entrepreneurs claim many of the looters were from organized gangs who took advantage of the tumult.

But others were previously law-abiding mothers and fathers who say they went out in search of basic foodstuffs because – in the almost total absence of official information or advice – they had no idea when the lights might come back on and feared their children would starve.

María Villalobos said she had spotted a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses among the marauders.

In a middle-class neighbourhood in west Maracaibo, an affable church-going businessman admitted he too had taken part in the looting of three nearby stores along with perhaps a third of his neighbours.

“Stealing – it’s a sin. It’s as simple as that,” he reflected, before pointing to his baby daughter and adding: “But … there was no information. The government said nothing. We didn’t know if it would last three days or a month.”

The man’s wife led their visitors into the kitchen of their modest, water-less home to show the deprivation she said explained much of the theft. On top of the fridge lay a potato and half an onion. Inside were seven bottles of milk, six of water, an almost empty bottle of ketchup and 10 small cartons of apple juice her husband had stolen from a supermarket.

“There’s no food,” she explained. There was no internet either because the community’s cables were stolen a year ago. Downstairs, six disposable nappies that had been drained of their gel and scrubbed cleaned for the umpteenth time hung from a washing line.

“The saddest thing of all is that this isn’t going to end here,” her husband predicted. “There could be another blackout at any moment and the same thing will happen again – or even worse.”

As the sun set over Maracaibo, María Corina Machado, a prominent opposition leader, arrived at an outdoor basketball court for a “citizens’ assembly” designed to energize the campaign to topple Maduro.

“We are, quite literally, living through our darkest hour. But these are also the brightest of times,” she told hundreds of supporters, some holding ‘Wanted’ posters stamped with Maduro’s face. “They have thrown everything at us. But we are still standing.”

As Machado spoke the lights went out again, plunging her gathering – and the rest of the city – into the shadows.

When she had finished speaking, illuminated by mobile-phone flashlights, supporters chanted “Freedom!” and headed back down gloomy streets to candle-lit homes.

Propaganda billboards vanished into the murk around them, their upbeat slogans obscured by the latest power failure: ‘Maracaibo is reborn!’, ‘Governing means fulfilling!’, ‘A secure future!’

The Guardian

Leave a comment