**The mysterious statues of San Agustín and underground tombs of Tierradentro, in southern Colombia, are finally rising from the dead after being off-limits for decades.**

**The mysterious statues of San Agustín and underground tombs of Tierradentro, in southern Colombia, are finally rising from the dead after being off-limits for decades.**

A decade ago, death stalked my drive to Parque Arqueológico Nacional de Tierradentro. The road from the town of Popayán over Colombia’s Cordillera Central mountain range was infamous for ambush and kidnap. Lonesome military posts hinted ominously at the presence of Farc guerrillas. I gripped the wheel tightly as I negotiated the unpaved road through a bleak, windswept Andean landscape, and cold fog swirled around me like a funeral shroud.

Thankfully, I arrived at one of the world’s largest necropolises alive. Unsurprisingly, I had the vast pre-Columbian hypogea of Tierradentro to myself.

South America’s largest trove of religious monuments and megalithic sculptures isn’t on Easter Island, nor even in Peru or Chile, as most travellers might assume. It’s Tierradentro’s 162 underground tombs carved into solid volcanic bedrock, and the more than 500 monolithic stone statues and tumuli (ancient burial mounds) surrounding the nearby town of San Agustín, sprinkled throughout 2,000 sq km of the serried mountains and highland plateaus of the Upper Magdalena Valley in southern Colombia.

These mementoes of an advanced, yet unknown (and unnamed), pre-Columbian, northern Andean culture had largely been off-limits during five decades of civil war. Now that the region is finally safe from Farc guerrilla activity, the awe-inspiring, yet little-known, Unesco World Heritage sites are easily visited and are guaranteed to amaze and inspire.

Eight years after my initial drive to Tierradentro, I arrived anew in the remote region and centred on the hamlet of San Andrés de Pisimbalá, amid a mountainous knot on the upper slopes of the Inzá Valley, 115km north-east of Popayán. From the twin (and tiny) Museo Etnográfico and Museo Arqueológico below the village, I followed a hilly and muddy trail that looped over surging mountain ridges, linking the five core concentrations of ridgetop tombs.

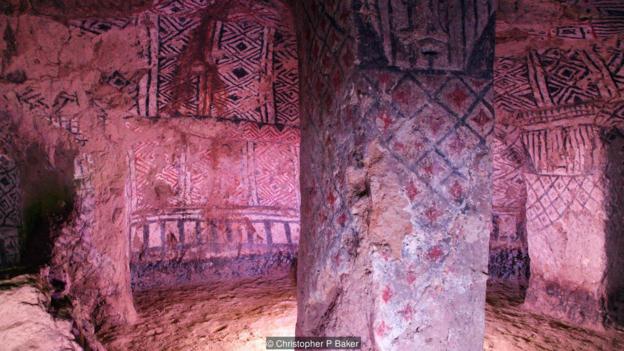

Staring into a black abyss at Alto de Segovia – the most impressive of the sites – induced lurching vertigo as I descended an elaborate spiral staircase drilling like a nautilus shell into 8m of andesitic tuff. I felt like Indiana Jones entering the Emperor’s Tomb. Below, the vast burial chamber measured some 12m wide. My torch illuminated walls and columns profusely adorned with geometric designs in black, yellow and ochre pigments, and human and animal figures danced in the flickering shadows cast as I roamed.

Another tomb was expertly carved to replicate a slanted roof and other elements of a pre-Hispanic wooden house: an allegory, no doubt, to prepare the deceased for the continuum between life and afterlife that was a sine qua non of the enigmatic society that carved these impressive funerary monuments.

Since the time of the region’s subjugation by Spanish conquistadors in the 1530s, the area has been inhabited by the Nasa, an indigenous group who speak páez (a Chibcha language). Yet little is known about the mysterious culture that flourished throughout the first millennium and then disappeared six centuries before the Spanish and the Nasa arrived on the scene. Although excavations began in the 1930s, archaeologists are still at a loss to explain who settled the region, where they came from or where they went. And no-one knows the relationship between the carvers of Tierradentro’s complex shaft-and-chamber tombs and, a 180km drive to the south-west, San Agustín’s earthen tumuli (burial mounds) and hulking statues.

The drama of the giant stone statue at whose base I stood seemed appropriate to its stupendous setting. It was weatherworn and smothered with blue-green algae. It towered above me some 5m tall – solemn, big-eyed, with a large scowling mouth.

The statue is one of a veritable army of colossuses and totems studding the plateau-like mesetas around San Agustín, a lovely colonial town close to the Ecuadorian border. About one-third are enshrined within Parque Arqueológico de San Agustín, comprising about 50 separate yet more-or-less contiguous ceremonial burial sites centred on the town that lends the entire collection its name.

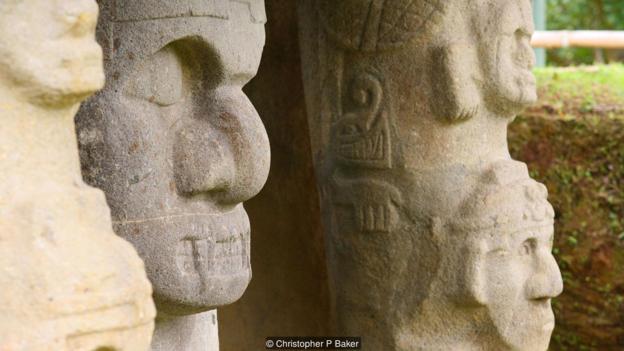

The majority of the statues were found within immense tumuli in which the pre-Columbian people buried their chieftains. They contour the meseta like a basket of eggs. My guide, Davido Pérez, knew every detail of every statue and the dolmens – stone sarcophagi topped by huge slabs within the tumuli – that most of them guard. Ferociously expressive and vital, the statues are so refined and well preserved they cut across barriers of culture and time. Pérez chattered away as we followed a trail that wound uphill to Alto de los Ídolos, the largest of the ancient sites.

“What you see is the legacy of an intense funeral cult,” Pérez said. “Death was viewed simply as a transition to another life.”

Hewn from relatively soft volcanic tuff, the statues – known locally as chinas – range in size from barely 20cm to 7m. Most were rectangular. Some were oval. A few were as hemispherical as if turned with a lathe. And most were etched with abstract motifs or zoomorphic figures, wrapping two-dimensional designs around three-dimensional objects to walk a path between worlds. Sunlight threw into high relief the exotic designs filled with tense, latent energy. Some resembled snakes, frogs and birds of prey – symbols of creation, wealth and power in pre-Columbian culture. Many were warrior figures with jaguar-type fangs – an allusion to chamánes (shamans), spiritual leaders who were thought capable of absorbing the jaguars’ power.

At the top of a large knoll, half screened by masses of overhanging foliage, we came upon a solitary statue – nicknamed Doble Yo (Double Self) – staring dead ahead, a perverse smile carved upon his lips. He wore a carved jaguar fur, its large head resting atop his own head and topped, in turn, by the skin of a crocodile. “This statue fuses male and female,” Pérez said. “It also symbolises the coupling of human and animal spirits upon which shamans relied for sorcery and power.”

“This one is vomiting,” said Pérez, pointing at a bulging-eyed figure. “He depicts the ancient practice of ingesting hallucinogens.”

The symbolic meaning of many other designs can only be guessed at.

The next day, our horses sure-footedly negotiated the steep trail that led downhill to a site called La Chaquira. Dismounting, we clambered down a staircase carved into the hillside to stand at a rock-strewn precipice overhanging the turbulent Río Magdalena. Waterfalls plunged from the far canyon wall. It was stupendously picturesque.

Pérez turned to point out petroglyphs etched on the massive boulders poised above the canyon rim. The largest displayed a male with hands thrown high, paying homage to Mother Nature's magnificent landscape.

Peering down into the gorge, I envisioned Spanish conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar and his ruthless army marching up the valley in the late 1530s after conquering the lands of the Inca. The indigenous Nasa put up a brave resistance but were no match for crossbows and muskets. They were driven into remote mountain redoubts. But the statues and tombs remained undiscovered until 1757, when Friar Juan de Santa Gertrudis stumbled upon the vast lithic library and called it “the work of the devil” as “The [natives] did not have iron or implements to produce such a thing.”

The tombs were looted centuries ago for their gold huacas (revered objects) and precious relics. And many of the original statues were lost or dispersed around the world. In 1899, for example, British anthropologists led by Captain H W Dowding loaded several dozen statues onto a boat bound for England. It promptly sank. Only one effigy was retrieved and transported to London, where it stands in the British Museum. Most extant statues are now anchored with concrete and rebar, but they still occasionally get spirited away. They’re in great demand on the illegal antiquities market and are now on the Red List of Latin-American Cultural Objects at Risk.

Despite its remoteness, I found this fertile centre of sculpture so compelling, and the once tense ambiance now so relaxed, my only risk was wanting to stay.

I lingered to enjoy the region’s cornucopia of other attractions: white-water rafting on the Magdalena River; exploring the Tatacoa Desert; a mountain drive to caves inhabited by nocturnal nightjars. As I once again negotiated an unpaved road through a wild, windswept Andean landscape, I found myself musing on how the dangers of guerrilla ambush are a thing of the past, and how San Agustín’s inscrutable statues and Tierradento’s dancing subterranean figures have finally risen from the dead after being off-limits for decades.

Source: BBC Travel

**UK24News**

Leave a comment